Crippling Economic Hardship Enflames Iranian Protests

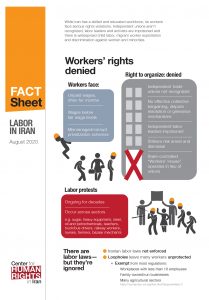

Protests in Iran over high inflation and unpaid wages are spreading in Iran as the working class and retirees struggle to make ends meet.

Protests in Iran over high inflation and unpaid wages are spreading in Iran as the working class and retirees struggle to make ends meet.

The largest organized rallies were held by retirees who are unable to support themselves on their small pensions. They were joined by workers struggling to make ends meet with low pay, late pay, and the growing prospect of unemployment.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects Iran’s inflation to rise to 39 percent in 2021 from 36.5 percent last year. Unemployment will also rise to 11.2 percent this year from 10.8 percent in 2020, while the stagnating economy, battered by sanctions and government mismanagement of state funds, is expected to grow by 2.5 percent.

The protests, mixed with angry slogans against ruling officials, are taking place while the country heads into a presidential election on June 18 with an extremely low projected voter turnout following a record low turnout in the February 2020 parliamentary elections.

According to Article 3 of Iran’s Constitution, the government is obliged to use its resources to create welfare and eliminate all forms of deprivation in nutrition, housing, employment, and health.

During the inception of the Islamic Republic leading up to the 1979 Revolution, Iranian authorities declared that the state was established to defend the poor and weak. Yet today it is the poor and working classes that are leading protests while the middle classfaces crippling economic economics.

According to the International Alliance in Support of Workers in Iran (IASWI), an advocacy group that tracks labor protests in the country, 1,915 protests occurred—mainly by workers, retirees, and teachers—between March 2020 and March 2021, a 50 percent increase compared to the previous year and the highest number in the past seven years, despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the Islamic Republic was established 42 years ago, it enjoyed the support of a large segment of the working class.

In March 1979, only a month after the revolution, its leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a decree ordering the new government to take firm steps to “eliminate shortcomings facing workers and enable them to live freely and comfortably like everybody else.”

In addition, Article 43 of the Iranian Constitution requires state support for the poor in nine broad areas “to secure the economic independence of society, to uproot poverty and deprivation, to fulfill the needs of human beings in the process of growth, while also maintaining liberty, the economy of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

Yet workers are protesting in the streets for basic rights including unpaid, meager salaries and disappearing health insurance. Meanwhile, blue-collar workers as well as students who’ve been disproportionately impacted by the economic crisis dominatedmedia reports of people increasingly taking their own lives in 2020.

Article 29 of Iran’s Constitution clearly states: “It is a universal right to enjoy social security and have benefits with respect to retirement, unemployment, old age, workers’ compensation, lack of guardianship, and destitution. In case of accidents and emergencies, everyone has the right to health and medical treatments through insurance or other means. In accordance with the law, the government is obliged to use the proceeds from the national income and public contributions to provide the above-mentioned services and financial support for each and every citizen.”

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which Iran is a signatory, requires states to provide all workers with “Fair wages and equal remuneration for work of equal value without distinction of any kind, in particular women being guaranteed conditions of work not inferior to those enjoyed by men, with equal pay for equal work,” and “A decent living for themselves and their families…” while recognizing “the right of everyone to social security, including social insurance.”

Article 11 of the Covenant states: “The widest possible protection and assistance should be accorded to the family, which is the natural and fundamental group unit of society, particularly for its establishment and while it is responsible for the care and education of dependent children.”

Yet in recent years, protests over unpaid wages continued to sprout throughout Iran.

Major, prolonged protests in the city of Shush in southwestern Iran at the Haft Tappeh sugar mill saw thousands of workers risking their freedom and lives to demand unpaid salaries and benefit payments.

State-enforced arrests, floggings, harassment, and persecution of many Haft Tappeh workers and activists did not deter other laborers around the country from organizing their own protests.

“Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, figures show that protests by workers have increased by 50 percent,” said labor activist Sattar Ramani, citing state media reports and data acquired from his own networks, in an interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) on April 23, 2021.

“Because of the virus, there was an expectation that written communication would replace public protests but in [the Iranian year] of 1399 (March 20, 2020 – March 21, 2021), protest letters sent to the authorities fell eight percent compared to the previous year,” he added.

According to Rahmani, one important change in the nature of the protests has been their gradual shift from the workplace to the streets and now frequently in front of relevant government buildings.

Some groups, such as teachers have also recently been more willing to travel from different cities to Tehran to rally in front of the Parliament building.

While noting that labor protests have become far more organized, Rahmani added, “These actions are made possible by the many anonymous workers who are helping to organize protests and strikes for basic rights.”

He added that as a result of strikes and protests in August 2020 at the Abadan, Qeshm, and Parsian oil refiners and at the Lamerd Petrochemical Company, all in southern Iran, workers were able to win some of their demands and inspired others to take action.

For example, there were major strikes—described by some labor activists as “unprecedented”—at the Tabriz Machinery Manufacturing Company in East Azerbaijan Province, especially during November and December 2020.

“Tabriz has a large middle class in comparison with other cities and there’s a strong culture there of helping the poor,” social researcher Oral Hatami said in an interview with CHRI on April 23. She added, “So when the people see more and more workers demonstrating and protesting against economic conditions, it says the working class is suffering and struggling.”

Hatami said protests by workers and retirees in the past were sporadic, unorganized, and limited to making demands based on labor laws and regulations. Recently, however, they’ve included strong and blunt slogans against senior officials.

Meanwhile, more than 250 rallies were held by retired Iranians in at least 20 cities during the past year, mainly to demand major adjustments to pension funds to offset skyrocketing inflation.

The government has so far failed to implement its promise of increasing retirement pensions by 130 percent in the new Iranian year that began on March 20.

At rallies organized by retirees, protesters have gone beyond economic demands. Many also called for a boycott of the upcoming presidential election.

“One of the important aspects of these rallies is the motivation to voice our concerns not just about our own issues but also about the general conditions affecting all the people,” Mr. Vaezi, a retired teacher in Mashhad, northeastern Iran, told CHRI.

“For many people of my generation these protests are an opportunity to demand not only our own rights but also the rights of our children and to call for a boycott of the (presidential) election,” he added, requesting anonymity for fear of reprisals by state agents for speaking publicly about the issue.

After Iran’s mass December 2017-January 2018 street protests, state forces became more ruthless in cracking down on dissent, culminating in a bloody response to major protests in November 2019, when hundreds of people were killed by police and security forces who were ordered to repress the demonstrations.

“In response to the many economic problems, a committee has been established to monitor the situation in accordance with a measure approved by the Supreme National Security Council,” said Hossein Zolfaghari, Iran’s deputy interior minister in charge of security, on April 21, 2021.

“In the past year, the economy and living standards have been hit by conditions brought about by the coronavirus,” he added. “It is increasingly affecting people’s lives and making it more difficult to maintain security.”

According to sociological researcher Oral Hatami, security concerns have recently led authorities to impose controls preventing the hiring of labor activists, notably at the Tabriz Machinery Manufacturing Company and the Iran Tractor Manufacturing Company, also in Tabriz.

“Those who want to get a job at these companies have to pass a lot of tests, which are designed to ensure that they won’t participate in protests and strikes, or to at least reduce the chance of labor unrest,” Hatami told CHRI.

Iran has also seen regular rallies by people who lost their retirement savings as a result of crashes in the Tehran Stock Exchange and failed investment schemes.

Read this article in Persian.