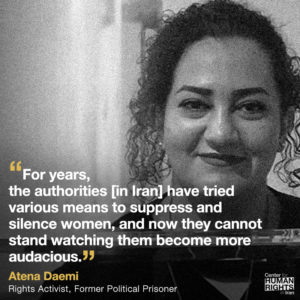

Interview: Atena Daemi was Jailed in Iran for Advocating Women’s Rights. Now She’s Free and Refusing to be Silent

When Atena Daemi was growing up in Iran and attending school in a religious-conservative neighborhood in south Tehran, she noticed the many ways in which women were treated differently than men. Girls had to cover almost every inch of their bodies and severly restrict their activities, while men could wear and do almost anything they wanted.

“Later… I realized that when I was not allowed to do something in the household, or when I insisted on my natural rights, I was in a way fighting for my rights as a woman,” she told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) in a Persian-language interview. “That’s why I and many others entered this path: to protest and oppose discrimination.”

For questioning the status-quo in the Islamic Republic and peacefully engaging in activism centered around various issues including children and women’s rights as well capital punishment, Daemi was imprisoned in her 20s under trumped-up national security charges.

She spent six and half years in three prisons throughout the country, where she was psychologically tortured, beaten, denied medical treatment, and harassed. Yet since being released in January 2022, she has refused to retreat into the state’s preferred role for her–subservient, domesticated, hidden–and has instead been outspoken about prisoners’ rights and the inhumane practice of child marriage.

“I spent seven years of my life in prison. My family suffered a lot. They were threatened and assaulted,” she said in the interview printed below, which has been edited for length and clarity. “Nevertheless, I shouldn’t be talking about my own problems. I should be the voice of other prisoners–now that I’m out of prison.”

CHRI: Why do you engage in civil rights advocacy?

CHRI: Why do you engage in civil rights advocacy?

Daemi: The most important issue that led me to the path of activism was the restrictions on women and girls, from the workplace to the home. When I was 14 or 15, I didn’t understand that the issues I was confronting were in the realm of human rights, specifically women’s rights. Experiencing these issues and restrictions wasn’t normal to me. That’s how I got involved in civil rights activities.

Later, when I got more deeply engaged in this field, I realized, for instance, that when I was not allowed to do something in the household, or when I insisted on my natural rights, I was in a way fighting for my rights as a woman. That’s why I and many others entered this path: to protest and express our opposition to discrimination.

CHRI: How would you describe the systematic restrictions on women in Iran?

Daemi: When women are in social environments outside the home, such as in school or at work, they notice that these restrictions are not personal but rather directed at all women. For example, I would hear from friends at high school that they had to get married for various reasons, despite their young age. They had problems studying and dropped out of school. When I witnessed these things, I saw a common suffering; a social problem. It wasn’t personal. It concerned all of us.

On the other hand, there was the issue of intolerance inside the family. I was raised in a neighborhood that was almost in south Tehran. Our school had a very religious climate and many things, like wearing the chador and prayers, were compulsory. Experiencing these things made me realize that the restrictions were not just being imposed on me alone, but on all girls.

Later in the workplace I faced other forms of discrimination and restrictions against women that also pointed to widespread inequality. The gender-based bias in the workplace, that gives rise to discrimination against women, made me realize how far-reaching this problem is.

Witnessing these various forms of discrimination and inequality gradually led to a series of questions: Why should women in Iran be subjected to so much injustice? Why should women be suppressed in so many ways? There are some men who oppose discrimination against women, but they go on with their lives as usual because they think the injustices have become “normal.”

CHRI: You and many fellow women activists were persecuted most severely by the state’s security and judicial establishments for your peaceful activities when you were in your 20s. Do you think the state reacted so harshly because you are a woman?

Daemi: First, I must say that the women’s struggle has a long history in Iran, more than a hundred years, long before the Islamic Republic. Many women in Iran have strived for their rights and our generation is only continuing those efforts.

The Islamic Republic wants to silence women by imposing discriminatory and unjust laws and by promoting a patriarchal point of view. The ruling establishment thinks it’s natural for men to protest and take political action, but it cannot tolerate women stepping into the same realm. The state wants women to be inside the home, to use them as cheap labor, to serve men. Men are also treated unfairly and given lengthy sentences for their civil and political activities. It’s interesting that there’s not much gender discrimination when it comes to issuing sentences.

But there were some differences in the security establishment’s approach towards women. It thought that by exerting greater security and judicial pressures on women, they would give up their activism inside prisons and the state would once again succeed in silencing them. But when they saw that this tactic didn’t work, they increased the pressures. That’s why it appears that the pressures on women prisoners are greater than on men…

In fact, we experienced the most harshness in prison. The authorities were horrified to see that their behavior had the opposite effect: Women would get more involved in political and civil issues; they wouldn’t be silent. The state doesn’t want to see this happen. For years the authorities have tried various means to suppress and silence women and now they cannot stand watching them become more audacious. That’s why women are treated worse compared to men. Women are not only suppressed in society, but also in prison…

CHRI: How did the authorities respond to you and other women prisoners’ peaceful protest activities while you were imprisoned?

Daemi: Based on what I have seen over the years, women who’ve stepped into civil rights activism have been more interested in action than theoretical discussions. This is completely unacceptable, as far as the Islamic Republic is concerned. We women have never had the opportunity to express ourselves in society and when we were forced to live our lives inside prison, we grew determined to continue our [civil rights] activities.

We took the position that we have freedom of expression, we have freedom of thought and decided we must defend our rights. Whenever something happened in the country, we felt we had a responsibility to react and do something. For instance, on various occasions, such as the November 2019 protests, we tried to hold a memorial, or we set up classes and conferences inside prison as a way of remaining engaged and learning from each other.

However, the prison officials and security agents couldn’t tolerate this situation. There were harsh security reactions against the men in prison, but the authorities thought it was easier to suppress the women. Yet despite these pressures, the women prisoners continued to issue statements and organize gatherings. The prison officials couldn’t exert complete control over the situation.

After the protests in December 2017 and November 2019, the number of women prisoners increased and the officials feared that the new arrivals would learn more about their rights and about civil rights activities and participate in our protests. This resulted in more pressures and many of us being banished to other prisons…

It came to a point that as soon as a new prisoner would arrive and sit next to us, and have meals and read books and talk to us, the Intelligence [Ministry] mole [who was ordered to spy on us] would quickly contact the prison guard and the new prisoner would be summoned to the office and questioned and warned about having meals with such-and-such prisoner…

The authorities kept repeating false accusations about us; that we were getting support from abroad or that we belonged to a certain political faction to frighten the other prisoners away from getting close to us. The authorities didn’t want us to come together or learn from each other and share our experiences.

One time, one of the prisoners was scheduled to be interrogated. Before her appointment, we talked, and I explained things I had learned about prisoners’ rights… I thought it would help her to know how to respond to the interrogator’s questions and actions. When she came back from the interrogation, she said the interrogator had asked if I had coached her.

These sorts of behaviors by prison authorities were aimed at creating discord and division among the prisoners, to break up our gatherings and friendly circles. When they realized that they weren’t going to succeed, and that all their pressures, harassment and threats had strengthened and increased our gatherings, they resorted to their last trick, which was banishing us to various prisons across the country and destroying the core group that we had formed inside [Evin Prison’s] Women’s Ward.

I must say that my banishment to other prisons was a good experience in some ways. It showed me a broader picture of women prisoners and their concerns. I was able to meet more women in prison and I tried to make them aware of their rights.

CHRI: Many people are unaware of the impact of being banished to a prison far from your home. Could you describe your experience?

Many people think it makes no difference which prison you are held in. But the prisoners and their families suffer. The prisoners also suffer from being separated from cellmates with whom they have shared a space for a long time. I was suddenly banished after a year of imprisonment and was put in a new prison with new cellmates. It was very difficult.

CHRI: Could you describe your experiences?

I experienced banishment on two occasions. Once in 2017 when I was banished [from Evin Prison] to Gharchak Prison. At the time, the prison authorities lied to me and Golrokh Iraee [fellow political prisoner]. They told us an expert wanted to meet us to discuss our case. But we resisted and refused to leave our cell and eventually they handcuffed us and took us directly to the IRGC’s Ward 2-A and said that the interrogator wants to have a word with us. We waited there for four hours and then they put us in a car and said we were going to the courthouse, even though it was nearby and there was no need to drive there. Then we realized that we were being banished to Gharchak Prison.

We didn’t have any of our personal belongings such as medicines, clothes, books, bank and phone cards… Why were we lied to? Why didn’t they show us a court order or give us a reason for their action?

When we arrived at Gharchak Prison… our impression of prisoners who had committed dangerous crimes completely changed. When we became their cellmates, we discovered the humanity inside those who had committed even the most violent of crimes. We saw how they could blossom under the right circumstances.

When you enter a new prison, there are several issues and problems to be dealt with one by one. You must make plans, get new appliances, and find new friends. You must learn about what the prison is lacking and think about… how to improve the conditions. Then you must explain your new situation to your family and prepare them on how to get used to it… We would try to explain the conditions to them so that they wouldn’t worry so much. At the same time, they had to travel a long distance to visit me and deal with new prison officials.

My second banishment was to Lakan Prison in March 2021, four days before the end of the [Iranian new] year. The difference this time was that I knew in advance that I was going to be banished again so I had collected all my belongings and was ready to go. The authorities had told me, and a few others, that we were going to be transferred. Nevertheless, it was a difficult time to be kept in limbo and we were getting separation anxiety from the thought of leaving cellmates at any moment. We could see the sadness in their faces, too…

When I entered the prison, I had no idea what to expect. Again, I had been put in a situation where I had to get familiar with a whole new environment and explain it all to my family. Again, I had to deal with the issues and problems of starting prison life from scratch…

Then there was the issue of getting to know the inmates in the new prison… When you are in a [ward for political prisoners], it’s easy to find prisoners to hang out with and talk to. Usually, they were already aware of their rights. They knew they had been imprisoned because they had made a conscious decision to protest discrimination. But when you are in a public ward, the conditions are completely different. You see many prisoners who were put behind bars because of lack of awareness. The experience of being cellmates with these prisoners gave me a much deeper understanding of their issues… including the hidden layers of discrimination in their lives.

During this period, many of the prisoners became aware of the country’s political issues. They became informed of the existence of protests and opposition. It became important to them, and they started to follow the issues. In the past, prison officials would come and make speeches and leave. But now, many of the prisoners were daring to ask questions, making demands and complaining about problems and how they were being treated.

Seeing this obviously gave me a good feeling, but the officials weren’t happy at all. In fact, the Islamic Republic’s plan to divide women political inmates in Evin Prison was a failure because the women could organize again in the prisons where they had been banished.

CHRI: The rights of women and children have been among your main areas of concern, even after your release from prison. You have been especially been outspoken about child marriage. What did you learn about it in prison?

Daemi: We were very restricted inside Gharchak Prison. We weren’t allowed to mingle and talk with other prisoners very much…

The situation in Lakan Prison was different. Due to its smaller space, the authorities couldn’t separate the prisoners. I tried to maintain my contacts with the prisoners in any way I could. I found opportunities to sit and talk with them. These prisoners had been incarcerated for various reasons, from murder to theft and [extramarital] relations. I talked to all of them and asked a series of questions.

What emerged was that, regardless of their crime, all were victims of child marriage. Some 90 percent of the women in Lakan Prison were either divorced or had been imprisoned for having relations outside marriage and killing their husbands.

I found it very strange that in a small prison like Lakan, with a maximum of 120 women prisoners, a large percentage of them had committed murder. This made me pay closer attention to why so many murders had been committed by women in a small provincial city. Most of them had killed their husbands. When I spoke to them, I tried to uncover some of the important secret layers of their lives, about the conditions inside their parents’ home, or the way they had been treated after getting their first period.

These conversations made me realize that the root cause of their current condition was often the predominance of patriarchal perspectives in the family and society. For instance, many of them had been married off at a young age only because girls are considered a financial burden. Many of them had been forced to get married between the ages of 10 to 16 with men whom they did not know. After marriage, they were prevented from going back to school and participating in society.

At first, they thought everything was okay but as the years went by and their lives began to change, they encountered a series of issues that made them think about transforming their lives. Since many of them didn’t have satisfying personal and sexual relations with their husbands, they had relationships with other individuals, which ultimately resulted in the husbands being murdered. Some former child brides had divorced their husbands but due to lack of sufficient support, had fallen into a life of crime, theft, or getting hooked on drugs.

When I examined these circumstances, I understood that they were all rooted in child marriage. The children of these women are also victims of child marriage.

One of the prisoners had been married at a young age to a boy as young as herself. After a few years, the husband started a relationship with another woman and his wife killed him out of anger. This shows that child marriage produce lots of victims and can wreck many lives.

Apart from this issue, one of my main activities was surrounding the death penalty and qisas (retribution as a form of legal punishment). When there were donation drives to save a person from execution with the payment of “blood money” to victims’ families, I would often hear that some people would refuse to donate because the killer was a woman who had killed her husband. I find this very sadd. I had met these women in prison and talked to them and knew that nobody knew about their troubled lives. They were abandoned, waiting to be hanged for “honor killings.” It’s awful.

I want to change this perspective toward women prisoners as much as I can. I don’t want to absolve anyone of their crime, especially when someone’s life has been taken away, but when there’s a problem that’s creating victims throughout the country, we must take a deeper look at the problem. Based on what I’ve heard from my friends, the situation is the same in other prisons as well. So, if the problem is widespread, we must look beyond the act of an honor killing.

Honor killings are tied to a series of constant problems and discriminations facing women in society, such as rampant child marriage, restrictions on women seeking divorce, and lack of support for those who are shunned by society after getting divorced.

I spent seven years of my life in prison. My family suffered a lot. They were threatened and assaulted. Nevertheless, I shouldn’t be talking about my own problems. I should be the voice of other prisoners—now that I’m out of prison.

CHRI: Do communication technologies help political prisoners reach the outside world?

Daemi: Undoubtedly there’s more information out in the public about the condition of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience now than before. I heard about this phenomenon when I was in prison, too, that society is a lot more informed. In the past, if we wanted to be the voice of a prisoner, there were a lot of obstacles in the way, and it became difficult. Now it can be done very easily and effectively through the internet…

Another important issue is that usually we hear the names of political prisoners more than other prisoners. There’s a kind of bias about the cases that are given public coverage… Political prisoners receive more attention than ordinary prisoners who represent a vast range of people who are ignored.

As a diverse group of political prisoners, we have always tried to represent the [Iranian] people as a whole. Therefore, I believe we should talk about and fight for the rights of all prisoners, too.

I was thrown into jail not because of my circumstances, but rather for opposing the death penalty and qisas (retribution as a form of legal punishment), and for advocating the rights of women and children. Now that I have been a witness to all the problems and issues inside a small prison environment, I’m confident that sharing my experiences can help eradicate the injustices against prisoners. It’s very important to share prison experiences.

CHRI: What do you think about Iran’s new “justice-seeking” movement?

Daemi: I don’t see the justice-seeking movement as only a reaction to the death of a loved one. I believe that discussions about all forms of suffering caused by the state against citizens are also a way of seeking justice. It’s very important for this to happen because we should understand that the Islamic Republic is not only responsible for killing people [during the protests of] December 2017 or November 2019. The Islamic Republic has been killing people in different ways with its laws, policies, and cultural dominance. It’s destroying lives in other ways.

Many of the crises created by the Islamic Republic in the past 40-something years will not go away with a superficial change in the political system. Therefore, for the future it’s very important to find and study the root of the problems very closely so that together we could heal the wounds caused by the Islamic Republic.

Read this interview in Persian

Find more of CHRI’s interviews with leading Iranian activists and thought leaders here.