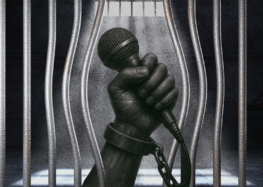

Killed Because You Are a Woman—Violence Against Women in Iran Reaches New Heights

Skyrocketing Femicides Fueled by Lack of Legal Protection Against Domestic Violence

Skyrocketing Femicides Fueled by Lack of Legal Protection Against Domestic Violence

(See end of article for publicly reported femicide cases in Iran in 2024.)

January 6, 2025—Killed by husbands or fathers for fleeing an abusive forced marriage, seeking a divorce, or allegedly “dishonoring” the family, women are being killed in Iran by male family members in alarming numbers, and the government of Iran is doing little to stop it, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) said in a statement today.

Skyrocketing intimate partner violence and so-called “honor killings” are taking the lives of an average of a woman every other day in Iran—and that represents only the small fraction of cases that are publicly reported. The Iranian government is complicit in this violence. Despite its obligation to protect its citizens from violence, it refuses to take available legal or practical measures to address a crisis that is affecting women across the country.

“Women in Iran are being shot, stabbed and burned to death by husbands and fathers in shocking numbers, but the government does not take even the most basic measures to try to prevent these crimes and the Iranian judicial system lets these cases go with little or sometimes even no punishment,” said Hadi Ghaemi, CHRI executive director.

The Islamic Republic’s laws and policies distinguish so-called “honor killings” from other murders and greatly reduce the penalties for perpetrators of the former. Authorities expend little effort to investigate such cases and there are no legal or practical mechanisms available to provide safety to women at risk.

“The international community must recognize the growing emergency in Iran—women and girls are being killed with impunity, and many more will be killed without the international community demanding that the Iranian authorities take concrete steps to address this violence,” Ghaemi said.

CHRI calls upon the Iranian authorities to take the following measures to address lethal domestic violence against women:

- End the legal distinction between “honor” killings and other murder charges in Iran’s judicial system, and pass effective and comprehensive laws against domestic violence.

- Fully investigate all reports of ill-treatment of women, and ensure survivors of violence and their families can access effective justice mechanisms that deter future crimes.

- Allocate resources for intervention mechanisms, including orders of protection, support services and safe houses, as well as educational initiatives to reduce domestic violence.

- Raise the legal age of marriage to international norms so that 13-year-old girls are not forced into marriages that too often end in lethal violence after they try to flee.

- Engage Iranian civil society in an extensive review of domestic violence, allowing experts meaningful policy input and addressing the dearth of data on the subject.

- Address issues faced by marginalized women (minority, refugee, and migrant women, women with disabilities, and widows) that magnify their risk of domestic violence.

Studies Document Alarming Increase of Murders of Women by Male Family Members

Reported cases of femicide (defined by UN Women as killings driven by “discrimination towards women and girls, unequal power relations between women and men, or harmful social norms”) represent only a small fraction of the actual cases in Iran.

There are no accurate statistics because so many cases of femicide go unreported, or are falsely reported as suicides and accidents. Yet every study undertaken so far indicates significant numbers of such killings in Iran—and that they are steadily increasing.

According to Stop Femicide in Iran (SFI), there were 93 known acts of femicide in Iran in just the first half of 2024, a near 60 percent increase over the same period in 2023, and 149 known femicides in 2023, averaging nearly one murder every other day. Husbands (or ex-husbands) were the primary perpetrators, and the methods they used were brutal—stabbing, immolation, suffocation, strangling, shooting, beatings, setting victims on fire, poisoning, running them over with a car, decapitation, and throwing women out of windows.

In addition to “honor” killings, women were murdered for requesting divorce, rejecting marriage proposals, or refusing second marriages. In about ten percent of cases, young girls were the direct victims of femicide. All age groups were affected but the majority of victims were under age 30, and children frequently witnessed the act. The murders occurred throughout the country, with Tehran recording the most cases.

Media sources inside Iran have also weighed in on the growing crisis. A report by Etemad Daily noted that in just the first three months of the Iranian calendar in 2024 (March 20 to June 21), at least 35 women and girls were murdered by their male relatives—25 percent higher than the same period in 2023 and 59 percent more than in 2022. This report also noted the victims’ husbands committed 85 percent of the murders and cases were spread across the country.

A report by the Iranian newspaper Shargh noted at least 165 women have been killed by their male family members in Iran since July 2021. Most took place in the Tehran province, contrary to the notion that femicides are more common in rural areas. The report stressed that number did not include cases in which women were forced by family members to commit suicide or cases in which women decided to end their lives to end domestic violence or child marriages. It stated 108 of these women were killed by their husbands, 17 by brothers, 13 by fathers, nine by sons, and 18 were killed by other family members such as their in-laws and cousins.

The Femena organization noted the Iran Statistics Center reported that in the first half of 2023, of the 52 cases of femicide officially recorded across various cities in Iran, 21 percent of the cases involved girls under the age of 18. The HRANA human rights news agency, meanwhile, reported that in 2024, there were at least 114 murders of women, and at least 16,264 cases of domestic violence.

Indeed, a pattern of domestic abuse of women often precedes femicides, but pervasive domestic abuse is woefully unaddressed in Iran. A broad academic analysis undertaken in 2021 of dozens of scholarly articles from 2000 to 2014 on domestic violence against women in Iran estimated its prevalence at 66 percent. The meta-analysis concluded, “After all [this abuse of women], there are no laws against domestic violence, despite all the damage it costs. All these efforts have come to an unlegislated bill [see section below] which has been reduced to a financial penalty.”

According to a study presented at a conference in Tehran hosted by the Imam Ali Foundation (now-shuttered by the Iranian authorities) on “Violence Against Women in Peripheral Families” in 2017, 32 percent of Iranian women in urban areas and 63 percent in rural areas experienced domestic violence. Other Iranian academic studies have indicated the rate is much higher. In any event, there is significant under-reporting, as domestic violence is typically suffered in silence, in a judicial context that provides no redress or support to women.

This unaddressed domestic violence in Iran—indeed, such violence is encouraged by laws that require women to obey their husbands and a judicial system that refuses to punish domestic violence—creates a context deeply conducive to femicides. The Lancet medical journal reported a shocking 8,000 “honor killings” across Iran between 2010 and 2014.

The Iranian government’s relentless suppression of civil society also contributes to the femicide crisis in Iran. The Lancet authors noted the connection between the growing numbers of femicides in Iran, and the refusal of the Iranian government to allow civil society to organize independently and peacefully advocate for social issues. It stated:

“Victims of honor killings are also victims of the weakness of civil society and advocacy institutions. How can one hope for the obsolescence of long-standing traditions when there is no room for civic activism and independent associations, and advocacy organisations have little opportunity to raise awareness among the public?”

Islamic Republic Laws Encourage Femicide

Saeid Dehghan, a prominent human rights lawyer who has defended numerous individuals in the courts of the Islamic Republic and who is director of the Parsi Law Collective, told CHRI:

“In the overwhelming majority of such cases, whether involving murder or other forms of violence against women, the real weapon is the existing laws of the Islamic Republic. These laws, rooted in religious doctrine and medieval perspectives, enable men in Iran—both within families and in positions of power in the government—to perpetuate such atrocities.”

Iran’s laws not only fail to provide women with the necessary protections against violence, they encourage the killing of women through lenient or sometimes nonexistent penalties for femicides.

Article 630 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code states: “Whenever a man sees his wife committing adultery with a man and knows that the wife has consented to it, he can kill both of them.” In an earlier interview with Deutsche Welle, Dehghan, explained, “According to this article, this kind of ‘honor killing’ is not punishable and the presiding judges usually use the phrase ‘the existence of an honorable motive to preserve honor’ during trial of such murders.”

Article 302 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code states that a man can legally kill a person for committing a crime that is punishable by death under Sharia (Islamic) law, such as adultery. (A woman in Iran, however, could never walk free after killing her adulterous husband and could be executed.)

Male family members are also shielded from the punishment of qisas (retributive justice) for their murders of daughters or granddaughters. Article 301 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code stipulates that the killing of a child by its father or paternal grandfather is exempt from qisas (which allows retribution in kind and thus a death sentence). Judges can still sentence a murderer to up to 10 years in prison, but in most femicide cases, the families and the prosecutors do not seek the harshest penalties, and judges often release the perpetrators after only a few years in prison.

Other aspects of Iran’s laws undermine preventative measures that could protect many women from their subsequent murders. Iran’s Civil Code forbids a woman from leaving the matrimonial home without the husband’s permission unless she is able and willing to go to court to prove she is endangered (Article 1114). This leaves women deeply vulnerable to violence, especially given the requirement of witnesses, the fact that a female witness’s testimony is worth half that of a man’s, and the stipulation that if a woman leaves the marital home, she forfeits her right to financial maintenance (Article 1108).

The Islamic Republic’s divorce laws also increase the potential for femicides. According to Article 1133 of the Civil Code, a man can divorce his wife whenever he wishes. Yet divorce rights for women are highly restrictive and, under Article 1130, if a woman desires a divorce she has to prove she is living in conditions of severe hardship that make marital life intolerable.

As put by Amnesty International, the “highly patriarchal judicial system that pervades Iranian courts means that in many cases women may not be permitted to divorce, even if they meet the requirements under the law. If they are allowed to divorce, the husbands invariably receive custody of their children.” In such a context, many women stay in dangerously abusive domestic situations.

Protective Mechanisms to Prevent Deadly Violence Sorely Lacking, Activists Persecuted

In addition to a legal framework that fails to address or effectively prosecute these crimes, Iran is also severely lacking in services and mechanisms to prevent such crimes against women.

Not only do the police not properly investigate femicides, typically dismissing them as a “family matter,” they often ignore cases of severe abuse and pressure battered women to return to their homes. Given the above stipulations of Iranian law, which requires that a woman who leaves the marital home not only forfeits her right to maintenance, but also loses custody of her children, women often return to their abusers, only to be subsequently killed.

Standard judicial mechanisms such as orders of protection or restraining orders aimed at preventing contact between abusers and their victims—not only after they have been explicitly threatened by family members but also even after severe domestic violence has occurred—are not available in Iran.

In addition, there are grossly insufficient services for victims or women at risk. Shelters and safe houses are absent in much of the country—a situation exacerbated by the government’s closure of facilities that address violence against women and the state’s persecution of relevant independent NGOs and charitable organizations.

For example, the Mehre Shams Afarid NGO safe house, which supported vulnerable women and children in Orumiyeh, in Iran’s West Azerbaijan province, was closed, and previously, NGOs in Iran such as the above-mentioned Imam Ali’s Popular Student Relief Society (IAPSRS), Khaneh Khorshid, and the Omid-e-Mehr Foundation, which also supported vulnerable women and children, were shut down. At the same time, activists advocating to protect vulnerable women and children are targeted by the state with bogus prosecutions and harsh sentencing.

Indeed, women often do not have any practical recourse even in the face of repeated abuse, given the arduous burden of proof that a woman must meet to report physical abuse, the lack of specialized training by law enforcement in domestic abuse, and the penalties she will endure for leaving the home. In such a context, it is not surprising that many women without any reasonable legal recourse who are repeatedly abused and are clearly under the threat of lethal violence, kill their husbands in a desperate act of self-defense. (They then receive no judicial consideration for the context in which their crimes were committed, but are instead sentenced to long prison sentences or execution.)

In a December 9, 2024, interview with CHRI, former political prisoner and human rights activist Atena Daemi recounted the stories of incarcerated women:

“I was a cellmate with these women [on death row for murdering their husbands]…99% of them were women who were forced to marry under the age of 18…. Most of these women endured continuous domestic violence as they went through childhood and adolescence and grew up. To escape this situation, they tried to get divorced, but they didn’t succeed… because they had children, getting a divorce became more difficult and they had to endure hardship for the sake of the children. But for many of them, tolerance became impossible, and at some point, and in the midst of a dispute, without any prior intention, they killed their husbands.”

Child Marriage Intricately Linked to Femicides

Widespread child marriage in Iran—in blatant violation of international law and Iran’s obligations under numerous international covenants to which it is a State Party—is intricately linked to femicides.

Girls can be married at age 13 in the Islamic Republic, and younger with the permission of the father or male guardian and a judge. The National Statistical Center of Iran stopped publishing information on child marriages, obscuring the ongoing crisis, but the latest available data shows that between the winter of 2021 and 2022, at least 27,448 registered marriages of girls under the age of 15 were recorded, along with 1,085 cases of childbirth within this age group. The true number of child marriages in Iran is much higher, as so many are not registered.

Zahra Rahimi, co-founder of the forcibly shuttered Imam Ali Popular Students Relief Society NGO, told CHRI:

“When the court does not allow marriages to take place [for example, if the girls are under 9 years old], the girls were sent into ‘temporary marriages’ until they turned 13, and then their marriage would become legal. For girls who do not have a birth certificate [often girls from Afghanistan or from underprivileged and marginalized communities], there are no accurate statistics. In many cases, there is no court process or legal registration of marriage; families only recite a verse from the Quran to seal the marriage contract.”

These girls, forced into marriages often with much older men, are thus subjected not only to marital rape but frequently sustained and severe physical abuse, to which there is no escape. These battered and abused girls are desperate to flee, and if they do, they are then vulnerable to honor killings.

Minorities, Women with Disabilities and Migrant Women Especially Vulnerable

Femicides affect all groups of women in Iran—cutting across ages, provinces, socio-economic status, ethnicity, and religion. Yet certain groups of women are more vulnerable than others.

Minority women face intense intersectional discrimination by authorities who are vital to the prevention, investigation and prosecution of domestic violence and femicides—the police, investigators, and judicial authorities—due to their gender and ethnic identity. They may also face linguistic barriers. These factors only magnify the obstacles they face in trying to seek protective services or justice.

Women and girls with disabilities experience domestic violence at twice the rate of other women. “There are no particular protections for women with disabilities in Iran’s laws [and] there are laws that make it easier to commit violence against them or prevent them from filing charges,” children’s rights lawyer Hossein Raisi told CHRI. “According to Articles 301 and 305 of the Islamic Penal Code, if the victim of a crime is ‘mad or insane,’ the perpetrator will not be punished by retribution. That means the life and well-being of persons with disabilities are worth less than a ‘sane’ person. In addition, emergency social services staff who respond to domestic violence complaints have not been trained to communicate with people with disabilities.”

Migrant and refugee women, who not only often face linguistic barriers, but also discriminatory treatment by police and judicial authorities, may also fear deportation if they press cases of abuse or murder.

LBGTQ individuals cannot press cases or seek any protective measures at all without exposing themselves to potential prosecution, given the illegality of same-sex relations in Iran.

Laws to Protect Women Languishing in Parliament for Over a Decade

Even as the number of femicides has soared, proposed legislation to try to better protect women from violence has been languishing in Iran’s parliament for well over a decade.

Initiated some 13 years ago, the “Preventing Harm to Women and Improving Their Safety Against Maltreatment” bill has been repeatedly passed back and forth between parliament, the government, and the judiciary, undergoing repeated modifications but never officially passed.

The latest version of the bill, which is considered to be hopelessly watered down, was introduced to the Iranian parliament in April 2023, but it has not even left the committee stage.

It is noteworthy that the Islamic Republic has been able to draft, revise and officially pass a new law mandating hijab, the “Law to Support the Family by Promoting the Culture of Chastity and Hijab” (see CHRI’s full English translation), which mandates the wearing of hijab in all spheres of life and imposes draconian punishments for noncompliance, but it has still not managed to pass a law protecting women from soaring lethal attacks.

Iran’s Lack of Protections for Women Violates International Law

Iran is one of only very few countries in the world that has not yet ratified the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

Moreover, the Islamic Republic does not meet its requirements to take clear steps to prevent violence against women and punish abusers under other international conventions such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Articles 3, 6 and 26) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Articles 3 and 12).

In addition, even though Iran approved the Convention on the Rights of the Child decades ago, it has not amended its laws accordingly, with the Islamic Republic’s refusal to revise its child marriage laws being one of the more egregious examples.

Publicly Reported Femicide Cases 2024 (as of January 2, 2025)

The following is a small sample of the cases of femicides occurring across Iran in just the last year. These cases represent those that were publicly reported; the vast majority are never reported—the perpetrators go unpunished and the unknown victims never receive justice.

- On January 1, 2025, it was reported that a man was arrested in the city of Nahavand, western Iran, after confessing to murdering his wife, 23-year-old “Zahra,” after she became pregnant.

- Ghazaleh Hodoudi, a 27-year-old woman who was set on fire on December 25, 2024, for refusing a man’s marriage proposal, died from her burns at Kowsar Hospital in Sanandaj, northwest Iran. Ghazaleh was set on fire at her workplace in the city of Naysar, near Sanandaj. Ghazaleh was “an independent woman who worked in a tailoring shop and spent her days with her 11-year-old daughter,” a relative told IranWire.

- On December 5, 2024, in the Miandoab district of West Azerbaijan Province, a husband murdered his two sisters-in-law. A source close to the Jediaat family told IranWire, “Mohadeseh Jediaat was a victim of child marriage. She had married a man who was severely addicted to drugs, and upon learning of his addiction, she pursued divorce seriously.”

- On November 23, 2024, a young woman named Halimeh Habibollahi, was murdered by her husband, who was also her paternal cousin. A source close to the family said, “Halimeh was a victim of child marriage and forced marriage. Throughout her years of marriage, she was constantly subjected to physical abuse by her husband. After killing her, he claimed that Halimeh had committed suicide, an entirely false assertion.”

- On November 18, 2024, after leaving his family for two years because of a dispute, a man returned home and murdered his 40-year-old wife with a gun and then took his own life in one of the southern neighborhoods of Tehran.

- On November 15, 2024, in Bahmai, a district in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, a man murdered his wife with a knife and then ended his own life. The motive for the murder, like many gender-based killings, was described as “domestic disputes.”

- On November 13, 2024, a woman was murdered by her husband in Marvdasht, southern Iran.

- On November 12, 2024, a lawyer in Tehran shot and murdered his wife and 12-year-old son before turning the gun on himself. The shooting took place in the Velenjak neighborhood of the capital.

- On November 10, 2024, a man was arrested in Ilam, western Iran, for murdering his 40-year-old wife. The police said the husband cited “family disputes” as the reason.

- On November 9, 2024, a man in Mashhad severely injured his wife’s head with a pickaxe during a family dispute. The woman was hospitalized.

- On November 9, 2024, Mansoureh Ghadiri Javid, a journalist with the state-run IRNA news agency, was murdered by her husband, who allegedly used a knife and blunt force. The perpetrator’s stated motive for the crime was “family disputes.”

- On November 3, 2024, a man was arrested in Bandar Abbas, southern Iran, after admitting to hacking his wife to death because of “severe family disputes” and burying her body on the side of a road nearly 500 km away.

- On October 24, 2024, the body of 26-year-old Fatemeh Amiri was found wrapped in blankets and a rug, stuffed into a closet, and abandoned near Chehelghaz Square, just outside Ghiamdasht, Tehran Province. A victim of child marriage, she had been stabbed and beaten to death by her husband. “Fatemeh endured 12 years in this marriage. Her husband was an addict and abusive. He would beat her over the smallest disagreements,” according to a source close to the Amiri family.

- On October 10, 2024, a man surrendered to the police in Mashhad northeastern Iran for murdering his wife on suspicion of adultery. The husband told investigators he thought his wife of ten years was having an affair with her cousin. The name of the victim was not released.

- On October 6, 2024, a man was arrested after confessing to killing his young wife “Mitra” at their home in Tehran. The victim went missing after a birthday party for one of her two children during which the couple had an argument.

- On September 28, 2024, a middle-aged woman in Shirvan, northwest Iran, was murdered by her husband.

- On September 24, 2024, a husband was arrested after admitting to murdering his wife “on suspicion of having a relationship with another man” in Shahre Rey, south of Tehran, according to reports.

- On September 22, 2024, a man in Rasht was arrested for the murder of his wife and mother of their two children, Matin Tayebikhah Foumani, along with another man, in the name of “honor killing” in Rasht, northern Iran.

- On September 17, 2024, a man in the city of Bonab, northwest Iran, murdered his wife and two of her family members. He cited family disputes as his motive.

- On September 8, 2024, a father murdered his 36-year-old daughter with a knife in Ilam, southwest Iran.

- On August 28, 2024, Mobina Zainivand, 17, was murdered by her father in Majin, western Iran. Eyewitnesses told IranWire that Mobina was at her grandmother’s house when a violent argument erupted over her marriage and her visit with a boy she liked.

- On August 28, 2024, Majedeh Khatoonbeigi, a 36-year-old woman from Ilam, western Iran, was murdered by her father. Majedeh was forced into marriage at a young age.

- On August 27, 2024, a man murdered his 18-year-old daughter with a hunting rifle in Dareh-Shahr, southwest Iran.

- On August 13, 2024, a man in Siahkal, northern Iran, murdered his 48-year-old wife with multiple blows to the head during a family dispute.

- On August 12, 2024, a woman was set on fire by her husband in Shiraz, because of “family disputes.”

- On August 9, 2024, a woman in Shahriar County, Tehran province, was murdered by her husband as he smashed her head on a vehicle during a “family dispute.”

- On August 7, 2024, a 22-year-old woman was stabbed to death by her husband in Zanjan, northern Iran.

- On July 31, 2024, a man in the city of Baharestan near Tehran, murdered his wife and three children, aged 1, 10 and 16. He then committed suicide.

- On July 31, 2024, a man identified as “Hassan M.” murdered his wife and sister-in-law in the village of Chenaran, northeast Iran. The killer’s motive for committing the crime was stated as “preservation of honor.” They were struck multiple times on the head with a stick.

- On July 27, 2024, Janeh Choupani, a 22-year-old mother of two from the village of Kozeh-Rash in Salmas County, northwest Iran, was strangled to death by her father on suspicion of adultery.

- On July 17, 2024, Ayda Heydarian, a 31-year-old woman from Sanandaj, Kurdistan province, was murdered by her husband with multiple stab wounds. The husband had a history of violent treatment of his wife.

- On July 16, 2024, Maria Shirmohammadi, a resident of the southern port of Bandar Abbas, was shot and murdered by her fiancé, after she rejected his marriage proposal. Her fiancé then committed suicide.

- On July 6, 2024, Marzieh Gholampour, a mother of one child, was shot and murdered by her husband in Bojnourd, northeast Iran. She was a victim of child marriage since the age of 14. Subjected to repeated violence, she was murdered after requesting a divorce.

- On June 23, 2024, Narmin Pirhaman, a 27-year-old mother of two, was stabbed to death by her husband on a street in Sanandaj, during an argument over her wish to get a divorce. Narmin was a victim of child marriage at the age of 14 and frequently subjected to domestic violence.

- On June 20, 2024, Narges Mousavi, 40, was murdered by her husband in a village near Rasht, northern Iran, with honor-related motives.

- On June 18, 2024, a man in Qazvin, northern Iran, strangled his 21-year-old wife to death following a “family dispute.”

- On June 16, 2024, Leila Paymard, 32, from the village of Khoranj near Piranshahr, northwest Iran, and a mother of two children, was murdered when she was set on fire by her husband, whom she was planning to leave because of domestic violence.

- On June 11, 2024, a man in Tehran stabbed his wife to death in front of their two young children.

- On June 5, 2024, a woman was stabbed and murdered by her husband in Tehran.

- On June 4, 2024, a man in Nazarabad, near Tehran, murdered his wife with blows to her head in a “family dispute.”

- On June 3, 2024, a middle-aged man in Tabriz strangled his wife to death with a charger cord.

- On May 19, 2024, Arezu Hosseini, a woman from the city of Eyvan, southwest Iran, was murdered by her husband in the name of “honor” with 100 stab wounds.

- On May 16, 2024, Kobra Delavar, 50, a retired healthcare worker from the Pahle Zarinabad District of Dehloran, western Iran, was murdered by her husband after being hit in the head with a blunt object.

- On May 16, 2024, a woman in Iranshahr, southeast Iran, was murdered by her husband using a gun.

- On May 7, 2024, a man in Mahdasht, near Tehran, strangled his wife to death and set her body on fire after a “family dispute.”

- On May 1, 2024, Shahin Goweli was murdered by her husband in Sanandaj, northwest Iran, because of her request for a divorce. The husband set her and himself on fire, and both died from the severity of their injuries.

- On April 24, 2024, a woman identified as Arezoo Shirkhani was murdered by her husband in Sabzevar, northeast Iran, using an axe.

- On April 16, 2024, a 42-year-old woman was murdered by her husband in Isfahan, central Iran. After being arrested, the husband stated: “I had a disagreement with my wife because I had remarried without her knowledge. I brought her to the garden and after an argument, I tied her to a chair and strangled her by putting tape around her throat.”

- On April 2, 2024, Bayan Amiri was murdered by her husband, who diverted the car carrying her and their 5-year-old child into the Darian Dam, near Paveh, northwest Iran.

- On March 26, 2024, a 34-year-old woman was murdered by her husband in the city of Juybar, northern Iran, due to a “family dispute.”

- On March 17, 2024, a man in Mashhad, northeast Iran, stabbed his wife to death in front of their two young daughters. During interrogations, he stated that a fight over cooking was his motive.

- On March 14, 2024, Maryam Razmjoo, a doctoral student in radiation oncology from Kermanshah, was shot and murdered by her ex-husband. Her mother, Paryush Bayat, also died in the shooting.

- On March 10, 2024, Ziba Sayyad, 27, a mother of two from the village of Hisarkani near Orumiyeh, northwest Iran, was shot three times and murdered by her ex-husband (cousin), ten days after their divorce.

- On March 8, 2024, a woman, approximately 37 years old, was set on fire by her husband, along with their eight-year-old child, in Tehran. The mother died after being taken to the hospital. Her child survived.

- On January 24, 2024, a 25-year-old woman was murdered by her husband with a gun in the city of Kowar, southern Iran.

- On January 18, 2024, a woman was murdered by hanging by her brother in Shiraz, southern Iran.

- On January 12, 2024, a 50-year-old woman in Tehran was set on fire by her husband and died after being taken to the hospital. Before her death, she told medical staff that her husband committed the crime. “My husband stopped the pickup truck and after getting out, he came to the passenger seat and told me let’s solve our problems and get a divorce. I said I have no problem with that. He took a bottle and poured the liquid on me. At first I thought it was acid, but it smelled like gasoline. Then he set me on fire.”

- On January 12, 2024, a woman named Nastaran was murdered with blows to the head with a rock by her husband in Tabriz, northern Iran. He cited “family disputes” as the motive for the act.

This report was made possible from donations by readers like you. Help us continue our mission by making a tax-deductible donation.