Reading Marx in Tehran (New York Times)

By MANSOUR OSANLOO, Op-Ed contributor, published in the New York Times

(June 13, 2013) IRAN’S presidential election on June 14 will be neither free nor fair. The candidates on the ballot have been preselected in a politically motivated vetting process that has little purpose other than ensuring the election of a compliant president who will be loyal to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Regardless of the outcome of the vote, the most urgent challenge for both the next president and Ayatollah Khamenei will be to confront a rising tide of discontent resulting from a rapidly deteriorating economic situation.

The outside world is primarily focused on whether the election will signal a shift in the Iranian regime’s stand on the nuclear issue. But for the average Iranian the most important issue is the impact of this election on her pocketbook — especially for the hardworking masses, whose purchasing power has drastically decreased as they struggle to provide the most basic necessities for their families.

Iran’s industrial workers, teachers, nurses, government and service-sector employees have been hit hard. The profound mismanagement of the economy by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s government, coupled with stringent international sanctions, has made these workers’ plight the most important aspect of Iran’s domestic politics.

The situation inside Iran may appear calm, because of the government’s harsh repression, but there are widespread workers’ protests. Dissidents from all walks of life, including educated but unemployed young people and women, are searching for any opportunity to express their grievances peacefully. Just last week in Isfahan, during the funeral of the prominent dissident cleric Ayatollah Jalaledin Taheri, thousands chanted “Death to the dictator” and “Political prisoners must be set free.”

The authorities in Iran are aware of the time bomb that the impoverishment of large segments of the population is creating. During a recent meeting of Iran’s National Security Council, high-ranking officials expressed their concern about possible uprisings of “the hungry.”

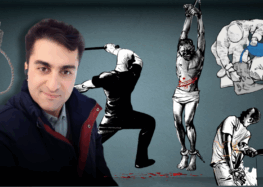

I know how far the authorities will go. I spent more than five years in prison for my labor-organizing activities. I was physically and psychologically tortured and threatened with rape. My interrogators also often threatened to detain, torture and rape my wife and children.

My son Puyesh was imprisoned and severely tortured. The authorities expelled my other son, Sahesh, from his university. Intelligence agents kidnapped Sahesh’s wife, Zoya, three times. She was beaten and threatened, and during one of these episodes, she miscarried. Tehran’s notorious prosecutor, Saeed Mortazavi, threatened my wife many times simply because she was pursuing my case with the judiciary. And my interrogators constantly harassed her with threatening calls and vulgar text messages.

For the slightest protest against my treatment, I was held in solitary confinement — once for 7 months and 23 days. Interrogators often threatened to kill me, telling me, “No one knows you are here, we can easily kill you with impunity.” They would remind me of the massacres of political prisoners during the 1980s and the many killed in detention since then.

But I was fortunate enough to have widespread international support, especially from international labor unions and human rights organizations. News about my case had an effect on my relationship with the prison guards. They were exposed to the news about my activism and reasons behind my imprisonment through satellite television channels and the Internet. As a result, their attitude toward me changed over time. I even forged friendships with some of my prison guards, themselves from working-class backgrounds, advising them on how to pursue work-related grievances against their employer.

I recently left the country because of death threats. But Iranian workers in many sectors are still organizing; some are publicly known, others remain under the radar to avoid the sharp sword of repression. Intimidation, prosecution and imprisonment of labor activists are rampant, but unions in Iran haven’t been fully silenced, and some have even had some limited success. My colleagues in the Tehran Bus Drivers Union managed to win an 18 percent wage increase, despite the imprisonment and firing of several of its members. Widespread unemployment, runaway inflation, shortages of essential goods and a precipitous decline in the value of Iran’s currency have had such a debilitating impact on workers and wage earners that they can’t afford to remain silent and indifferent.

In the face of this economic crisis, none of the current candidates on the ballot has put forward a tangible economic plan that addresses workers’ concerns. They have made references to difficulties and criticized the Ahmadinejad administration’s mismanagement and corruption, but they have not proposed or discussed any solutions to the workers’ plight.

We welcome international support from all those who care for our struggle. The American left has rightly opposed military adventurism against Iran, but it should also oppose sanctions that hurt ordinary Iranians and back our struggle to gain the freedom of speech and association, as well as the right to bargain collectively and advocate for workplace improvements. Those basic liberties are essential for our dignity — and for the future of genuine democracy in Iran.

Mansour Osanloo, a former president of the Tehran Bus Drivers Union, was imprisoned by the Iranian government from 2006 to 2011. This essay was translated by Hadi Ghaemi from the Persian.