Khuzestan Teachers Say Disallowing Mother Tongue in Schools Is Causing High Dropout Rate

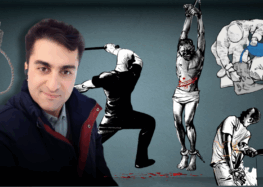

Photo Legend: Disallowing usage of mother tongue is not limited to classrooms in Khuzestan Province. It also includes recess and activities outside the classroom, and if a teacher acts against it, he/she will be reprimanded and dismissed. Photo from Fars News Agency.

In an interview with the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, two former Khuzestan Province teachers who currently live outside Iran said that the government’s refusal to allow the teaching and speaking of Arabic in schools has led to poor grades and an increase in dropout rates among Khuzestan students.

According to these teachers, the Ministry of Education and Development has a policy of forcing school principals to give passing grades to the students in this region, but Ministry officials cover up this policy so that the consequences of disallowing mother tongues in schools is not revealed publicly. This policy has led to the emergence of a group of students who can never compete successfully with students of other regions of the country in nationwide examinations. Only a small percentage of Khuzestan students can pass the annual university entrance examination, which would allow them to have access to higher education.

According to these two teachers, Abdolla Mazraeh and Karim Dahimi, forbidding the use of the mother tongue is not only limited to classrooms in Khuzestan Province. The policy is also continued during school recess and in activities outside the classroom. If a teacher tries to answer students’ questions about their schoolwork in Arabic even outside the classroom, the teacher is reprimanded and dismissed.

Ali Asghar Fani, the Interim Minister of Education and Development, discussed the subject of the use of different ethnic groups’ languages in Iranian schools last week. In an interview with Jamaran website on October 3, Fani promised that Iranian schools would be allowed to teach students in their ethnic tongues. In his talk, Fani referred to Rouhani’s Statement Number 3, which stresses education in the mother tongue of Iran’s different ethnic groups, as well as implementing Article 15 of the Iranian Constitution, which addresses teaching different ethnic tongues. He said that allowing the use of ethnic languages in schools is one of his priorities. Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, according to official procedures within the Ministry of Education and Development, teaching in mother tongues at schools in non-Farsi-speaking regions is prohibited.

Abdollah Mazraeh, a former teacher of elementary and middle schools in Khuzestan Province, was dismissed from his job by the Ministry of Education after 18 years of teaching because he did not observe the Ministry’s required procedures. He lives in Turkey now. Mazraeh received a BA in Educational Development from Tehran’s Tarbiat-e Moallem University in 1993 and was officially employed by the Ministry of Education. “They told me directly that because I was acting against the educational laws and speaking in a non-Farsi tongue in class, I was dismissed,” he told the Campaign.

“Let me tell you honestly, in every 50-student class in [a Khuzestan] high school, a maximum of 9 will enter the university, and those are students with good strong memory and high intelligence. I am of Arab descent myself and I grew up in the Arab region. All my family members spoke Arabic and until middle school I couldn’t understand Farsi, and I had passed my classes only because I had a strong memory and could memorize the courses. I couldn’t comprehend my textbooks and couldn’t understand what the teacher said in class. This is a prevalent problem among students in Khuzestan Province. The different language is the biggest factor in holding back Arab students; they have no intelligence deficit as compared to Farsi-speaking students,” Mazraeh told the Campaign.

Asked what portion of students in Ahvaz can comprehend and speak Farsi, Abdollah Mazraeh told the Campaign, “It varies from region to region. For example, in Ahvaz schools, because of its urban situation and the non-Arab population traffic there, the students understand Farsi, but in other regions on the margin and in villages of Khuzestan, students don’t understand Farsi at all. I can tell you that students there only memorize the courses without understanding what the teacher or the textbooks are saying.”

There is a contradiction between this fact and the academic statistics among Arab-speaking students. Though most Arab-speaking students score low grades throughout the year because they don’t comprehend Farsi and can’t understand the material they are being taught, they score passing grades at the end of the academic year and advance to a higher grade.

Karim Dahimi, a former teacher and school principal from Ahvaz who has become a human rights activist, told the Campaign, “I was a middle school principal for a while and saw closely that in the numerous meetings the Education Ministry managers had with us, they kept telling us that they only wanted a percentage of the students to pass. Of course they never told us directly that we had to give passing grades to the students, but they always told us that we had to find a solution for it. After the end of the academic year I had to personally report the percentage of passing students to the Head office and when the officials saw my report which indicated there were several students who had failed subjects or who had failed the entire grade, they wouldn’t accept my forms and asked me to ‘correct’ my forms. They would tell me that I had to give passing grades to everyone and re-submit the forms.”

Dahimi was a math and science teacher in Ahvaz and Shoosh in Khuzestan Province for ten years. He moved to London two years ago. “We have students in the middle school who are still unable to write their names and last names correctly. I mean they have not learned the Farsi alphabet correctly yet. How have they been able to make it to middle school without learning the alphabet? There were always some teachers who resisted this demand from the Education and Development Office and wouldn’t give passing grades, but most students were given passing grades at the last stage,” Dahimi said.

Karim Dahimi told the Campaign that the interaction between the students in Khuzestan region and their non-Arab teachers is riddled with misunderstandings. “Many of the teachers who teach in Khuzestan Province schools have come from other provinces and don’t speak Arabic. The non-Arab speaking teachers are incapable of understanding the students in class and sometimes even further insult the students…When the students don’t understand what the teacher is saying in class, and the teacher doesn’t understand Arabic either, things leads to feelings of anger and insult on both sides,” said Dahimi.

Asked how the authorities would find out if a teacher speaks some Arabic sentences behind the closed doors of a classroom, Dahimi told the Campaign, “Those who work in the developmental areas of schools are quite aware of this. Also, students unintentionally tell other teachers that such and such teacher speaks Arabic with us and we understand what he means, and this is how the news becomes public and there are lots of people who wish to object to this or report it to the office.”

On June 3, Hassan Rouhani published a statement on the subject of teaching the ethnic mother tongue of Iranians (Kurdish, Azeri, Arab, etc.), officially emphasizing his intention to fully implement Article 15 of the Iranian Constitution which concerns teaching the mother tongue at schools and universities. Article 15 states: “The official language and script of Iran, the lingua franca of its people, is Persian. Official documents, correspondence, and texts, as well as text-books, must be in this language and script. However, the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed in addition to Persian.”