Is UN Engagement Having an Impact on Iran’s Human Rights? Absolutely.

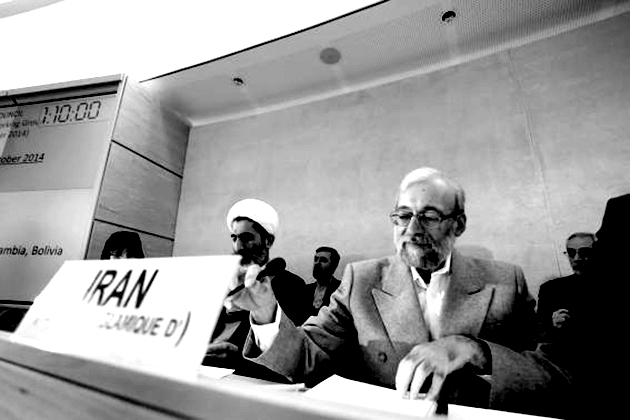

To critics who question the ability of UN processes to change the behaviors and policies of the leadership in the Islamic Republic of Iran, an English language media interview with a top Iranian official has provided a revealing answer.

In an interview broadcast last Friday, a Euronews reporter asked Mohammad Javad Larijani, the head of the Iranian judiciary’s Human Rights Council, if he was “proud” that Iran leads the world in executions per capita. In response, Larijani said:

“Not at all, we are very much unhappy and uneasy about that… and we are trying hard to change the laws which are bringing that situation about.

As you know and I [have] said several times […] more than almost 80% of these executions [are] stemming from narcotic drug related crimes. I think if we change the law [on narcotics], 80% of our executions will be dropped.

This is the first pragmatic stage to bringing down the numbers of executions.”

To a veteran Iran observer, Larijani’s answer stunned.

Larijani’s hint of a potential policy shift in Iran’s human rights practices with regards to capital punishment is a significant departure from his previous comments on the matter. From July 2013 to June 2014 alone, at least 852 individuals were reportedly executed in the country. Despite these statistics, as recently as this past March, Larijani remained staunchly committed to Iran’s use of the death penalty and went so far as to say that the international community should be “grateful” for Iran’s increased execution rate. While Larijani has, in the past, expressed personal concern over the mandatory death sentencing laws for drug offenders, he has stopped short of characterizing this as a government-wide position, much less an issue in need of reform.

Amendments made to Iran’s Anti-Narcotics Law in 2011 mandate the death penalty for anyone in possession of 30 grams or more of certain types of illicit drugs. Aside from this harsh legal reality that penalizes the sale and smuggling of narcotics the same as possession, the sharp rise in executions for drug-related offenses in the past few years can also be attributed to another amendment in the Anti-Narcotics Law, which essentially permits Iran’s top prosecutor to deem a sentence final and enforceable and thereby circumvents the need for the Supreme Court to review and endorse the sentence.

The UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Iran, Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, as well as other UN thematic rapporteurs, have, time and time again, voiced concern over Iran’s broad use of the death penalty, in drug-related cases and otherwise, as clear violations of international law.

There is scant evidence to show that the rising number of executions for drug-related offenses – either 80% or 90% of all executions per Larijani’s own estimates – is actually helping to curb Iran’s drug problem, or deterring would-be traffickers from continuing to smuggle opium and heroin from Afghanistan to Europe via Iran.

While the position of the Iranian authorities has long been defiant, with the argument that the specter of the death penalty is necessary to deter potential perpetrators from engaging in the drug trade, recent indications suggest that Larijani and other officials realize that the political cost of the current policy outweighs any benefits.

According to sources close to the discussions between the Iranian authorities and UN human rights officials the country’s leaders realize that change to mandatory death sentencing for drug crimes is needed. Last month, during the presentation of his report on Iran to the UN General Assembly, Ahmed Shaheed remarked that Iranian authorities were currently reviewing the efficacy of use of the death penalty for drug offenses, and welcomed that development.

Additionally, there are suggestions that the Iranian populace has tired of the ease with which death sentences are meted in the country, particularly for moral offenses. In previous years, public executions in the country were crowded, almost festive affairs, but public awareness campaigns dedicated to ending executions in Iran, such as the Iranian anti-death penalty group Legam, have led to reduced attendance numbers. Also, the growing popularity of online campaigns to raise funds to pay “blood money” to victims’ families to pardon and thereby save the lives of persons sentenced to death, in accordance with the Islamic law of Qesas, is a telling indicator of the public’s decreased appetite for capital punishment.

That the Iranian authorities are now taking drug laws under review is a testament to the sustained advocacy of Iranian civil society activists and organizations that have worked for decades to abolish death penalty laws. The efforts of these human rights defenders—in tandem with UN processes that seek to hold Iran accountable to its obligations under international law—have yielded some gains in limiting the use of stoning in execution, and temporarily at least, in respect to the execution of juveniles. It now seems that when it comes to the use of the death penalty for drug-related crimes, restrictions on its application may be trending in a similar direction. Also, and arguably more importantly, the efforts of these defenders have gone beyond simply impacting UN mechanisms and have helped bring about a cultural shift inside the country in respect to the societal view and approach towards execution.

Short of abolishing the death penalty for drug-related offenses in total, even minor adjustments to the minimum drug possession amounts that mandate execution could result in preventing hundreds of individuals a year from facing the gallows. In light of Larijani’s recent comments, and the UN efforts in this regard, that now seems to be a distinct, and hopeful, possibility.