Public Outcry in Iran Over Plan for Increased Morality Police Prompts Review

Deploying 7,000 undercover morality police in Tehran contradicts the principle of the presumption of innocence, Iranian lawyer Ali Rambod told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

“We should move towards interpreting laws on the basis of innocent until proven guilty,” he said. “It appears this principle has been overlooked in regards to the undercover police force.”

“There is an incorrect assumption that people are somehow walking time-bombs that are about to commit crimes at any moment,” added the Tehran-based lawyer. “Implementing this plan would create a sense of insecurity and mistrust among the public.”

The announcement of the formation of a special force to bring “moral security” to the capital was first made by Tehran’s police chief Hossein Sajedinia on April 18, 2016.

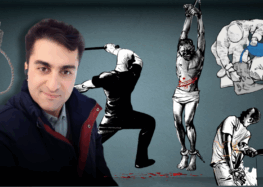

Iran’s notorious morality police, a branch of the security forces co-directed by the Revolutionary Guards and the Interior Ministry, routinely subject Iranian men and especially women to harassment and arrests for alleged inappropriate public behavior.

“In the past two years, the police have monitored four different offenses: sound pollution (loud music), dangerous driving on highways, harassment of women, and removing the hijab in the car,” said Sajedinia. “These were the main things we dealt with.”

Following the public outcry over the plan, Sajedinia described the 7,000 undercover agents as “members of the police force who will assist their colleagues on their time off (in civilian clothes),” during an interview that aired on Iranian state television on April 20, 2016.

Five days later, the acting Interior Minister Hosseinali Amiri said that the government had decided to review the plan.

“It is very important for the Interior Ministry to make sure these kinds of plans take people’s concerns into consideration and prevent any potential abuse,” he said on April 25, 2016. “Therefore, it has been decided that this plan will be sent for review to the National Security Council and the National Social Council.”

The plan has been met with widespread pubic criticism, especially via social media in Iran and abroad. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has also publicly questioned the intentions of those who support the move.

“Some wake up in the morning and think about how to secretly control people. Others want to do it openly. Do we have the right to do that?” asked Rouhani during a cabinet session on April 20, 2016.

“Individuals or Institutions can’t just arbitrarily try to control the people,” he added. “You cannot limit the people’s freedoms with directives and unilateral initiatives by some agencies.”

The plan’s estimated financial cost has been heavily criticized in the Iranian news media. The undercover agents would cost roughly 70 billion rials (about $2.3 million USD) per year just for one hour of work per day based on the national minimum wage, reported the reformist Etemad newspaper on April 23, 2016.

The plan was also criticized by Iran’s Vice President for Women and Family Affairs Shahindokht Mowlaverdi.

“I fear that if this plan is carried out, it would be reduced to confronting those who are improperly dressed and become a nuisance to women rather than protecting them from molesters,” said Mowlaverdi via a post on her Telegram page that was quoted by the reformist Azad News Agency (ANA) on April 22, 2016.

The plan has also been criticized from within Tehran’s security establishment.

“There has been no coordination with the government for implementing this plan,” said Mohsen Nasj Hamadani, Tehran Province’s deputy official in charge of police and security, on April 22, 2016. “Tehran’s provincial administration has some issues with it, which we better clarify before it is wrongly implemented.”

“We should not expect such a plan to succeed without coordination with other state security organs,” he added. “It would be better if our colleagues in the police force do the necessary coordination with relevant agencies so that everyone can work together to promote virtue and prevent vice.”

On the other hand, a number of Friday Prayer leaders have defended the proposed move in their sermons.

“It is expected from the honorable and decent people of Iran, particularly those in Tehran Province, to observe the Islamic hijab. To make sure of this, the police force is deploying thousands of undercover agents who will promote virtue and prevent vice in a very respectful and calculated manner,” said Tehran’s Friday Prayer leader Mohammad Ali Movahedi Kermani on April 23, 2016.

“I believe those who do not observe the hijab properly want to insult the state. I have seen them and felt embarrassed,” he added. “The police should undoubtedly confront those who openly commit sin, otherwise they would be sinners themselves.”

Hardliners in Iran frequently complain that officials are not doing enough to preserve their ideals of public morality; they are especially preoccupied with the way women wear the state-mandated hijab.

Ahmad Alamolhoda, the ultra-conservative Friday Prayer leader of Mashhad, Iran’s second largest city, also dismissed Rouhani’s criticism that the undercover police force would undermine the people’s freedoms and privacy.

“How would the [undercover police force] be interfering in people’s public or private lives? If the police catch a thief, is that considered interference in people’s lives? If they arrest a murderer, is that interference in people’s privacy, too?” said Alamolhoda on April 23, 2016.

Tehran-based lawyer Ali Rambod told the Campaign that the morality police do in fact undermine Iranian citizens’ constitutional rights.

“Let’s assume that some people commit crimes. We have laws on how to confront them. Legislators have been very specific on how to pursue those who do not observe the hijab or play loud music and so forth. Specific conditions must be met to bring punishment. Law enforcement agents can report a crime to judicial authorities and then pursue it based on orders issued directly by judicial officials… Law enforcement is not everybody’s job,” he said.

“It will cause a lot of legal controversy if we use some people as so-called undercover police without proper qualifications or clarification of their responsibilities while giving them great power to determine and deal with certain crimes,” added Rambod. “As a lawyer, I don’t think this plan would be in the public interest.”

Rambod also told the Campaign that Iranian law grants citizens the right to request identification to determine the authority of anyone claiming to be an undercover agent.

“We are not like some Eastern European countries of yesteryear that had their secret police,” he said. “Our law enforcement officials must operate with clear identities and responsibilities.”

Bahman Keshavarz, the former chairman of Iran’s Bar Association, also criticized the plan from a legal perspective on April 19, 2016.

“It is for a judge or a judicial official to determine whether someone has violated the law on the hijab… What is ‘proper’ or ‘improper’ can be very different and contradictory depending on one’s viewpoint,” he said.