Commentary: Iran’s Hard-Liners Crack Down as Their Base of Support Narrows

This commentary was originally published in the World Politics Review.

Hadi Ghaemi

There is a crackdown underway in Iran. But it is no longer just a crackdown on dissent. Rather it is an attempt to crush views or expressions that depart from the insular and rigid worldview of an increasingly small band of hard-liners.

It is not opposition parties, secularists or even reformists that are the latest targets of repression, but longtime insiders and scions of the Islamic Republic; a conservative and clerically vetted president and his administration; and revered cultural figures whose music, art and writings have long been the pride of Iranians.

These are the new targets of repression, and they are indicative of a shifting domestic political context in Iran in which the base of the regime is shrinking, the range of permitted views is narrowing, and the gulf between the state and society is widening. As a result, this base is fearful and reactive. It is made up of the Revolutionary Guards, intelligence and security agencies, the judiciary, hard-line members of Iran’s parliament, ultraconservative clerics, and above all the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Perhaps they have cause for concern. At every opportunity, the Iranian electorate has used its limited powers of political participation to elect centrist officials who eschew vitriol against the world, welcome conflict resolution, and seek the country’s international economic integration and revitalization.

Iranians elected Hassan Rouhani to the presidency in June 2013 by a large margin. They backed the Rouhani administration’s efforts to reach a nuclear deal with world powers, concluded in July 2015. In February’s elections to parliament and the Assembly of Experts, the clerical body that will select Iran’s next supreme leader, Iranians voted in significant numbers for centrist and reformist candidates allied to Rouhani, despite efforts by hard-liners to block all but their own candidates.

This moderate center is anathema to the hard-liners, who prefer international isolation and vilification of the West—all the better to maintain control over the country’s narrative, legitimize their repression, and sustain their dominance at home.

Thus after each of these electoral junctures, the circle of repression has widened. Activists and human rights defenders like Bahareh Hedayat, Narges Mohammadi and Abdolfattah Soltani have been joined in prison by reformists—and then by journalists and internet professionals, and later by anyone who expressed independent views on social media. Writers,artists, musicians and poets whose work didn’t conform to ultraconservative cultural views have been targeted next, followed by members of the Rouhani administration’s inner circle and professionals working within it. Dual nationals who recently traveled to Iran—such as charity worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Homa Hoodfar, a professor of anthropology at Concordia University in Montreal—have been detained too, as part of the strategy to supposedly prevent so-called Western infiltration. And the judiciary capped these growing arrests with harsher and longer sentences.

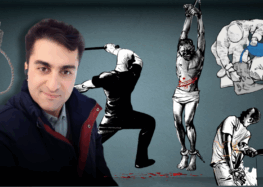

The tactics of repression follow a familiar pattern. Threats, arrest, prolonged detention without charge—typically incommunicado and in solitary confinement, with access to counsel denied. Convictions are handed down in a brief, closed trial in which the sole “evidence” is a forced false “confession,” elicited during solitary confinement under intense pressure and threats. The prison sentences are long, during which the prisoner will be subjected to particularly harsh incarceration conditions—including the denial of medical care—due to his or her status as a political prisoner.

There has always been tension in the Islamic Republic between electoral legitimacy and Islamic legitimacy.

The battle between the moderate center in Iran and hard-liners has become an existential one, and its outcome is not certain. While Rouhani and the moderate forces he represents have the backing of a majority of the electorate, hard-liners hold the institutional levers of power, including the office of the supreme leader.

There has always been tension in the Islamic Republic between electoral legitimacy and Islamic legitimacy. But in another marker of the shifting domestic political context in Iran, this relationship has come under increasing strain. Electoral authority, defined by the officials who are voted into office, and Islamic authority, defined by official clerical bodies and ultraconservative clerics who hew to the views of Khamenei, are increasingly in conflict. Each represents forces whose views are diverging more starkly. The electorate chooses moderation; the official clerical bodies try to block or void these choices.

The 2016 elections saw unprecedented numbers of candidates, largely representing reformist forces, disqualified by appointed clerical bodies such as the Guardian Council. With the power to vet all candidates, the council made little pretense of transparency, disqualifying thousands of candidates with rationalizations such as “no time to review their applications.”

Moderate and centrist forces, understanding the power of electoral legitimacy, re-grouped, making an effective end-run around this vetting by quickly forging alliances with lesser-known centrist or pragmatic conservative candidates—essentially, anyone but the most conservative candidates. They grouped themselves under party lists such as the “Omid,” or Hope, list, using social media to push voting for the entire list.

The strategy largely worked. Indeed, the Omid list swept all of Tehran’s 30 seats for parliament.

Hard-liners attempted a few swipes after the fact—blocking, for example, the seating of one female reformist lawmaker, Minoo Khaleghi, after she was elected to parliament. But the outcry was fierce, and so far, others have not been disqualified in a similar manner.

There were also reports of electoral “irregularities”: suspicious wins by candidates who were trailing in the vote counts; the prohibition of reformist gatherings and unchecked attacks against reformist candidates by vigilante groups; and suggestions of voters being bought and bussed in to polling stations. But this was not on the scale of the 2009 presidential election that resulted in Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s second term in office. It would seem the authorities did not want a repeat of the huge peaceful protests that followed that widely disputed election, which were violently put down by the state.

In addition to this tug of war between elected and clerical bodies, a third trend is discernible: Unelected state bodies are operating alongside the elected administration as a kind of parallel, unaccountable government. This kind of shadow government is controlled largely by the Revolutionary Guards, answers directly to Khamenei, and has increasingly usurped a number of the powers from Rouhani’s administration. For example, the Revolutionary Guards’ Intelligence Organization has taken the lead in arresting massive numbers of individuals. It has also targeted members of the Rouhani administration, including with cyber attacks, eclipsing the authority of the Ministry of Intelligence and Ministry of Interior.

Against this backdrop, there are still some positive trend lines. Indeed, compared to the rest of the region, there are quite unique ones. Iran’s population is young, educated and connected digitally to the world. Iranians demonstrate a strong appetite for engagement and moderation, and a willingness to work steadily, peacefully and through the electoral process for gradual change. Perhaps this is what the hard-liners fear the most.

Hadi Ghaemi is the founder and executive director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.