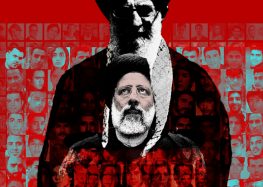

International Law Expert Denounces Iranian Presidential Bid of Rights Violator Ebrahim Raisi

The candidacy of Ebrahim Raisi in Iran’s May 19 presidential election “shows great contempt for human rights, the rights of the Iranian people, and the families of those killed in the 1980s,” international law expert Shadi Sadr told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

In 1988, Raisi was part of a four-man panel—with Hosseinali Nayeri, Morteza Eshraghi, and Mostafa Pourmohammadi—that ruled on the extrajudicial executions of thousands of political prisoners.

“With Raisi’s candidacy, the regime is sending a clear message that it does not care about crimes against humanity nor does it have any intention to investigate the crimes in 1988, and in fact will install those responsible for the massacre in the highest governmental posts in the country,” said Sadr, who was based in Iran until 2009.

“Under international law, what happened to the victims of the 1988 massacre falls under ‘Enforced Disappearance’ because the locations of the crimes and places where the victims were buried were never disclosed.”

“The families were never notified and the crimes have been covered up with lies and deceit,” she added.

To date, no one in Iran has been held accountable for the mass executions.

“It was very contemptuous towards all the families who lost loved ones in the 1980s, especially in 1988, for President Hassan Rouhani to appoint Mostafa Pourmohammadi as minister of justice [in 2013],” said Sadr. “At the time, many wrote letters to Rouhani to complain about it, but of course it did not make any difference.”

Established in 2010, Sadr now heads Justice for Iran, a Germany-based organization that aims to “address and eradicate the practice of impunity that empowers officials of the Islamic Republic of Iran to perpetrate widespread human right violations against their citizens, and to hold them accountable for their actions.”

Raisi’s Rise

Raisi, 56, officially registered for the presidency on April 14, 2017.

Later referred to as the “Death Committee,” the panel he served on in 1988 was created by the late founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who ordered the executions of thousands of political prisoners after the panel interviewed them.

The victims, who had already been tried and were serving prison sentences, did not know they were facing death when they then faced the inquisition-like proceedings.

In a statement announcing his candidacy, Raisi said he wanted to rectify the “wrong culture in the management of the country” as president.

Raisi began his career in Iran’s judiciary in the early 1980s and was deputy prosecutor of Tehran when he served on the four-man panel in 1988.

He was promoted to the deputy head of the judiciary in 2004 and held the post until 2014, when he became prosecutor general for a year.

In 2016, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei appointed Raisi to head Astan Quds Razavi, one of Iran’s wealthiest religious institutions that effectively functions as a major business conglomerate.

Crimes Against Humanity

“Experienced international lawyers have investigated the 1988 massacre and most of them believe it was a crime against humanity and among the most serious crimes the world has seen,” Sadr told CHRI.

“If someone commits such crimes and is provided immunity for political reasons in his own country, he will not be immune from justice according to today’s international laws,” she added. “However, it is difficult to prosecute the 1988 crimes in international courts.”

Sadr explained why it’s difficult to prosecute Iranian human rights violators in other countries.

“It’s not impossible, but the first problem is that Iran has not signed significant human rights conventions that include mechanisms to prosecute human rights abusers, namely the UN Convention against Torture, and Iran is not a member of the International Court of Justice,” she said.

“Secondly, when the 1988 crimes took place, international law had not progressed very much and there were no mechanisms to hold human rights abusers accountable like we can today,” continued Sadr. “And since the laws are not retroactive, crimes committed in the past cannot be prosecuted.”

“Raisi, Pourmohammadi, Eshraghi and Nayeri’s role in the 1988 massacre is clear, and with the release of the audio file of Ayatollah Montazeri’s meeting with the four, there are no more doubts left,” she added. “But even if they travel abroad or become residents of other countries, it will be hard to put them on trial for what happened in 1988.”

At that time, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, who was the heir apparent to then Supreme Leader Khomeini, told the panel: “I believe this is the greatest crime committed in the Islamic Republic since the [1979] revolution and history will condemn us for it…. History will write you down as criminals.”

Montazeri’s son, Ahmad, released the taped recording of that conversation in an audio file posted online in August 2016, bringing the massacre to the forefront of public memory.

As punishment for releasing the tape, he was sentenced to six years in prison in 2016 by the Special Court for the Clergy, which Raisi headed as chief prosecutor.

The Intelligence Ministry also tried to suppress and confiscate the recordings.

Ahmad Montazeri is currently on furlough (temporary leave) and told CHRI he has more files to release when the time is right.

If Raisi becomes Iran’s president, he would have immunity from prosecution.

“International laws and conventions extend diplomatic immunity to political leaders and officials, and as long as they remain in their posts, they cannot be prosecuted in international courts or in other countries,” she said.

“They cannot be prosecuted even if they travel to another country because of diplomatic immunity,” she added.

It remains to be seen how Raisi’s past will affect his presidential campaign.

“You might not be able to prosecute a president whose role in widespread human rights violations has become clear,” Sadr told CHRI. “Nevertheless, it’s a shame for any country for its highest official to be known as a human rights abuser.”

“There will undoubtedly be a lot of political opposition and pressure against governments who invite him over to their countries,” she added. “For someone with that kind of background, becoming president will certainly not be without costs.”