Denied Due Process, Detained Telegram Channel Admins Go on Hunger Strike

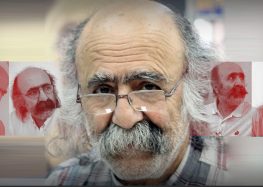

Telegram channel admin Nima Keshvari was detained in mid-March 2017 by the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization.

Six administrators of channels on the Telegram messaging application who were arrested in the run-up to Iran’s May 2017 presidential election have gone on hunger strike in Evin Prison to protest their prolonged detention without access to legal counsel.

An informed source told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) that no charges have been issued against the detainees—who supported President Rouhani’s recent re-election bid—more than three months after their arrests by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in March 2017.

“Lawyers have come forward to defend them, but the prosecutor’s office and the judge have not allowed lawyers to see the prisoners according to a recommendation by the IRGC,” the source told CHRI.

“Legal representation becomes official after a client signs a document delegating his or her lawyer,” added the source. “This has not occurred yet.”

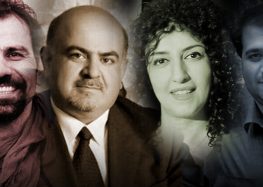

Ali Ahmadnia, Mojtaba Bagheri, Sobhan Jafari-Tash, Javad Jamshidi, Nima Keshvari and Saeed Naghdi began a hunger strike on June 19, 2017 in Evin Prison’s Ward 2-A, which is controlled by the IRGC.

Their case is being tried at the Revolutionary Court in Tehran presided by Judge Abolqasem Salavati.

Attorney Ali Mojtahedzadeh told the semi-official Iranian Labor News Agency (ILNA) on June 21 that he was assisting Keshvari and Bagheri upon requests from their families, but his requests to meet them in the prison have been denied.

“The accusations mentioned in their case are related to their activities in support of the [Rouhani] government,” added Mojtahedzadeh. “You cannot accuse people of acting against national security when they are cooperating with the government.”

The centrist administration of President Hassan Rouhani, who maintains close ties with reformist factions, has been publicly criticized by the IRGC for refusing to censor some of Telegram’s features.

Rouhani has also resisted pressure from hardliners to ban Telegram ahead of the March 2016 parliamentary elections and the May 2017 presidential and local council elections.

According to Telegram, some 40 million people use the app, mostly on their mobile phones, in Iran.

Between March 14-16, 2017, agents of the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization rounded up eight admins of 12 Telegram channels aligned with reformist factions that supported Rouhani’s bid for a second term on May 19.

Two were soon released, but six remain in detention and were forced to hand over control of their Telegram channels to the IRGC, which deleted all the content.

Nearly two weeks after their arrests, on March 26, Rouhani responded to calls by reformist members of Parliament for an explanation by asking the Interior Ministry to investigate the “suspicious arrests of a number of media activists on the eve of the elections.”

To date, the ministry has not made its findings public and judicial officials have not commented other than to announce that the admins were arrested in connection with alleged “security issues” and “indecent acts.”

“Regarding this particular case, there are matters that relate to the intelligence minister himself (Mahmoud Alavi) and therefore he cannot comment on this case or prepare a report about it,” said the judiciary’s Spokesman Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei on April 12.

“I don’t know of any crime that the admins may have committed for which I share responsibility,” Alavi replied hours later. “It looks like they may have been arrested because of me.”

Alavi, was appointed to head the Intelligence Ministry by Rouhani.

CHRI has obtained an Instagram photo showing the minister posing with some of the detained admins. The Instagram account has since been shut down.

Frustrated by the lack of due process in their loved ones’ cases, families of some of the detainees lodged a complaint on June 6 with Parliament’s Article 90 Committee, which is in charge of investigating public grievances.

According to Article 90: “Whoever has a complaint concerning the work of the assembly [Parliament] or the executive power, or the judicial power can forward his complaint in writing to the assembly. The assembly must investigate his complaint and give a satisfactory reply. In cases where the complaint relates to the executive or the judiciary, the assembly must demand proper investigation into the matter and an adequate explanation from them, and announce the results within a reasonable time. In cases where the subject of the complaint is of public interest, the reply must be made public.”

According to CHRI’s source, the committee has not released the result of its investigation.

Thirty MPs wrote a letter to Alavi on May 30 asking him to explain why the admins had been under prolonged detention without legal counsel in violation of the Constitution.

“A number of pro[Rouhani]-government Telegram channel admins who were arrested in the run-up to the presidential election remain in legal limbo more than two months into their detention,” said the letter.

“Based on information we have received, these individuals have not been charged within the legal time limit under Article 32 of the Constitution and have been denied a lawyer in violation of Article 35.”

On June 6, Alavi responded to the MPs’ questions in a closed session of Parliament, but the deliberations have not been made public.