Iran’s Child Protection Bill Includes Kids With Disabilities But Fails to Close Legal Loopholes

A bill in the final stages of Iran’s legislative process addresses the country’s legal vacuum regarding the abuse of children with disabilities but includes loopholes that put those children at risk, according to experts.

A bill in the final stages of Iran’s legislative process addresses the country’s legal vacuum regarding the abuse of children with disabilities but includes loopholes that put those children at risk, according to experts.

Article 3 of the “Bill For the Protection of the Rights of Children and Youth”mentions children with disabilities as an example of those in perilous situations while Article 20 calls for more severe punishments against employees convicted of abusing those children.

The bill was first drafted nine years ago. On July 24, 2018, lawmakers overwhelmingly approved the bill’s outline, which aims to protect minors from violence, abuse and harassment. But the bill includes language that enables offenders to evade punishments.

“The inclusion of the phrase ‘not intended for disciplinary purposes’ will give an open hand to judges to permit certain kinds of abuse that could specifically affect children with disabilities,” a lawyer specializing in disability rights told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

“Many families who beat up and verbally abuse their children with disabilities or lock them away at home, give the excuse that they could not control them any other way or that they wanted to protect them from abuse by others,” added the source.

Article 1 describes child abuse as: “Any deliberate action, or inaction, endangering or harming the physical, mental, moral and social health of children and young people, such as battery, incarceration, sexual abuse, disparagement or threats that are not intended for disciplinary purposes, or the placement of children and young people in difficult or unconventional situations, or the refusal to give them assistance.”

At the same time, proposing more severe punishments for those who abuse children and young people with mental or physical disabilities is a positive aspect of the bill.

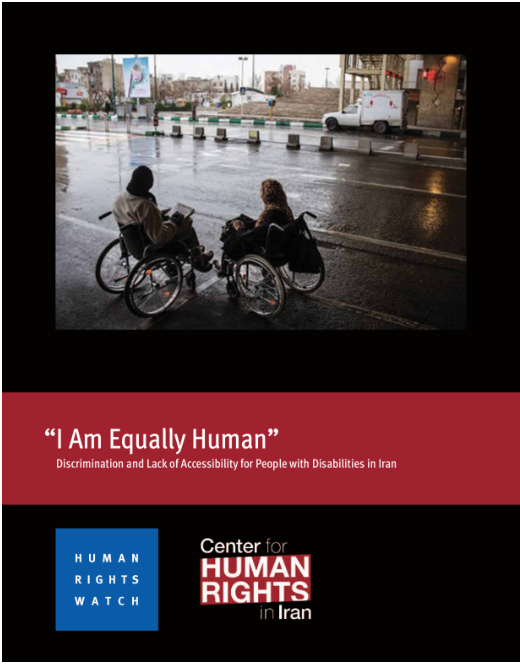

The 72-page report, “‘I Am Equally Human’: Discrimination and Lack of Accessibility for People with Disabilities in Iran,” documents the everyday barriers people with disabilities meet when going to government offices, healthcare centers, and when using public transportation.

Punishable offenses include the exploitation of children with disabilities for the purpose of begging, using them to traffic drugs or other contraband goods, sexual exploitation and buying or selling their organs.

The law also specifies punishments for abuse by people charged with caring, educating or training children, including in Section 9 of Article 20, which deals with abuse in rehabilitation centers.

However, Article 6, which details the responsibilities of the agencies that provide services for people with disabilities in Iran, makes no mention of children with disabilities.

According to the disability rights expert who spoke with CHRI, this article should have, for example, required training for the State Welfare Organization’s social workers and all others involved in child care, to protect children with disabilities from violence.

The bill also lacks enforceable measures that would enable children with disabilities to report instances of abuse or mistreatment to independent and credible authorities.

Another glaring omission from the bill is training for emergency response workers, the police, the judiciary and health staff on how to communicate with children with disabilities.

The bill also fails to address the need for the judiciary to handle cases of abuse against children with disabilities without prejudice and doesn’t require judicial staff to receive training to learn how to communicate with these children.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “children with disabilities are almost four times more likely to experience violence than non-disabled children.”

The WHO continues, “Factors which place people with disabilities at higher risk of violence include stigma, discrimination, and ignorance about disability, as well as a lack of social support for those who care for them. Placement of people with disabilities in institutions also increases their vulnerability to violence. In these settings and elsewhere, people with communication impairments are hampered in their ability to disclose abusive experiences.”

Iran does not provide statistics about the abuse of children with disabilities. In March 2018, Reza Jafari, the head of the country’s Emergency Social Services, said 16,000 cases of child abuse had been reported to his organization in the previous six months. Jafari did not give any further details.

But news reports regarding child abuse cases within homes or at care centers in Iran indicate the prevalence of the hidden problem.

In its May 2017 report on Iran, the UN’s Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) said Iran should address and improve the “lack of disaggregated data about access by girls and boys with disabilities to health services, education, an adequate standard of living including social protection and enjoyment of sports, leisure and cultural activities.”

Despite these recommendations, the Law for the Protection of the Rights of Persons With Disabilities, ratified in April 2018, did not address violence against persons with disabilities, in particular, the problems faced by children with disabilities, prompting some activists to call for a separate law to specifically address this issue.