Iran Set to Execute Third Individual Sentenced by “Corruption Court” For Alleged Economic Crimes

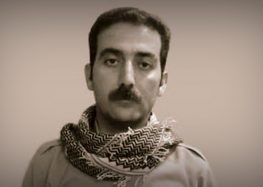

A defendant addresses Judge Abolqasem Salavati, who’s notorious in Iran for issuing harsh sentences in politically sensitive case.

Two Men Already Executed, 1,700 Others Summoned Since Courts Set Up Four Months Ago

Iran’s Supreme Court has upheld the death sentence issued against Hamid Bagheri by the country’s new “corruption courts” system and handed it down for enforcement, the Chief Prosecutor of Tehran Province Gholam-Hossein Esmaili announced December 11, 2018.

It is not clear whether the accused had access to legal counsel.

If the sentence is carried out, Bagheri would be the third person to be executed by order of the courts, which were set up by Iran’s judiciary and approved by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in August 2018 to try individuals accused of economic corruption.

At least 1,700 people have also been summoned to the special courts, of which 540 were banned from leaving the country, 424 formally charged, and 133 detained, the capital’s Chief Prosecutor Abbas Jafari Dowlatabadi told reporters on December 11.

Two of the five people who had been sentenced to death since the court was set up four months ago—Vahid Mazloumin and Mohammad Esmail Ghassemi—were hanged in November.

The Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) has condemned the courts for gravely violating the right to due process and the right to a fair trial in Iran.

133 People Jailed by Corruption Courts in Four Months

According to the state-funded Mehr News Agency, Bagheri was sentenced to death by Judge Abolqasem Salavati—notorious for issuing harsh sentences in politically sensitive cases—for the charge of “committing corruption on earth by way of the fraudulent sale of 322,343,336 kilograms of tar in a network of several individuals as the CEO of Jey Oil Co. www.jeyoil.com.”

Based in Tehran, Jey Oil describes itself as the largest producer of tar in the Middle East.

The case included 33 other defendants, five of whom had fled the country, Mehr reported.

Meanwhile, Dariush Ebrahimian Bilandi and Younes Bahaeddini are awaiting the outcome of their appeals against their death sentences issued by the special court for economic crimes in Fars Province on November 6 for the charge of “organized disruption of the country’s banking and economic network.”

Since the courts were set up in late summer, some 133 people have also been jailed, 50 of whom were convicted of currency-related crimes,” Dowlatabadi said.

“We would’ve had greater problems if the judiciary had not taken action against recent corruption,” Dowlatabadi added. “The enemies want to accuse the Islamic Republic and its officials of corruption. Therefore we must strongly press forward.”

In addition to the corruption courts’ denials of the rights to due process and a fair trial, and the state’s assumption of guilt that they reflect, these courts have been established in a context of growing violations of law by the Iranian judiciary.

The refusal of the judiciary to defend citizens against rights violations by the state; the blanket approval of routine denials of due process and a fair trial; the intensified restrictions on counsel that now allow defendants in any “national security” case to pick only from a list of state-approved attorneys; and the growing number of lawyers the judiciary has put behind bars for trying to defend their clients, all speak to a judiciary that has dismissed any obligations to follow the rule of law.

The United Nations and the European Union have repeatedly called on Iran to address serious violations of due process and the right to a fair trial.

“These corruption courts represent yet another arena of judicial abuse in Iran,” said CHRI’s Executive Director Hadi Ghaemi.

“The judiciary is supposed to defend the law—and citizens’ protections under that law,” he added. “Instead, the Iranian judiciary is leading the way in trampling citizens’ rights and defending the system that allows this.”

Iranian Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi also condemned the courts in an interview with CHRI on November 13, 2018, describing the quick prosecution and heavy sentences as “a masquerade of justice.”

“Instead of implementing justice, the state is pretending to be seeking justice, meaning that …judicial procedures, bringing charges, the right to legal counsel — none of these things are clear in these cases,” she said.