Nasrin Sotoudeh and Baha’i Political Prisoner Refuse Phone Calls in Solidarity With Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe

Authorities Revoke Phone Privileges, Reduce Food Rations in Evin Prison’s Women’s Ward

Authorities Revoke Phone Privileges, Reduce Food Rations in Evin Prison’s Women’s Ward

Two political prisoners held in the same ward as Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe in Iran’s Evin Prison have given up their right to phone calls until the authorities lift newly imposed restrictions targeting the Iranian UK dual national as well her fellow inmates in the Women’s Ward.

Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s weekly phone calls with her husband were canceled and her food rations decreased after she announced she would be going on hunger strike for access to medical treatment for lumps in her breast. This prompted prominent human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh and Baha’i university educator Azita Rafizadeh to give up their own phone calls in solidarity with Zaghari-Ratcliffe.

Until recently, female inmates held in the Women’s Ward of Evin Prison in Tehran were allowed to make three 20-minute phone calls per week. Now, female prisoners can only make 10-minute phone calls according to a schedule set by the authorities, a knowledgeable source told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

In the wards where male prisoners are held, inmates have phone access every day from eight in the morning until nine in the evening, added the source who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

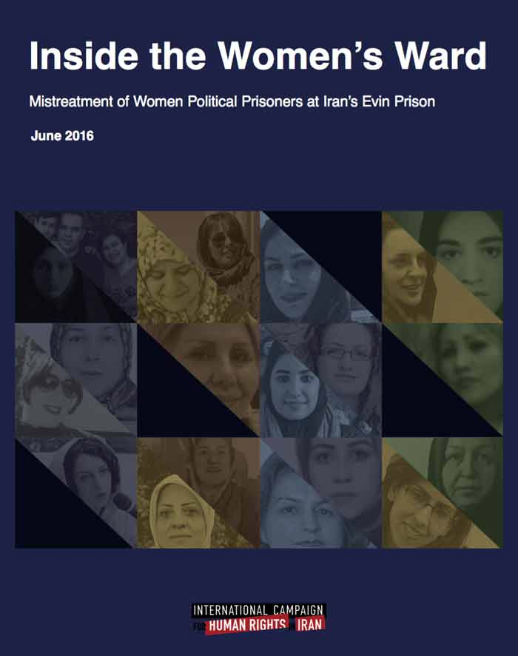

Inside the Women’s Ward: Mistreatment of Women Political Prisoners at Iran’s Evin Prison

According to testimonies provided by former political prisoners held in Evin Prison’s Women’s Ward, inmates there endure inhumane conditions, including the denial of proper medical care in a prison infirmary that is dirty and lacking in supplies and medical specialists, denied or delayed transfer to hospital and specialists for treatment of serious illnesses, inadequate nutrition, and intermittent lack of heat.

Like all political prisoners in Iran, these women are subjected to harsher treatment than other inmates. They are routinely denied or subjected to limited family visits and telephone communication with family, and they are denied or subjected to limited furloughs, or temporarily leave, granted to most prison inmates in the Iranian penal system.

The behavior consistently cited by the inmates as the most distressing of all was the denial or limitation of visits and telephone communications with family. This is in keeping with the Islamic Republic’s punitive treatment of political prisoners throughout the country’s prisons.

As a number of the prisoners of the Women’s Ward are mothers, including Zaghari-Ratcliffe, Rafizadeh and Sotoudeh, the lack of phone access is particularly painful given the unique bond between mother and child.

Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s daughter is now four-years-old; having spent more than half her life in Tehran being raised by her grandparents (Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s parents) after the authorities imprisoned Zaghari-Ratcliffe under a five-year prison sentence under unspecified espionage charges.

Sotoudeh has an 18-year-old daughter and a 12-year-old son. Rafizadeh has a nine-year-old son and her husband, Payman Koushk-Baghi, is also incarcerated.

Since October 2015, Rafizadeh and Koushk-Baghi have been behind bars serving five-year prison sentences for teaching at the Institute for Higher Education (BIHE), which provided university-level education for members of the Baha’i faith who are routinely denied university educations in Iran because of their religious beliefs.

Sotoudeh, an outspoken human rights defender and lawyer, is also currently serving a five-year prison sentence while facing several other charges primarily for being the attorney of a woman who was charged for removing her compulsory headscarf in public in Iran.

On January 8, 2018, Iranian state-run TV aired a sensationalist film posing as a documentary alleging that Zaghari-Ratcliffe was an agent of the US and UK who was plotting to bring down the Islamic Republic.

The film was shown in the Women’s Ward.