Images of Resistance: Photographers Who Documented Iran’s Woman, Life, Freedom Movement

“No one had weapons; our only weapon was our mobile phones, capturing and sharing images.”

“No one had weapons; our only weapon was our mobile phones, capturing and sharing images.”

Iranian Photographers Captured the Government’s Brutality and the Protesters’ Bravery

September 16, 2024 – To mark the second anniversary of Iran’s Woman, Life, Freedom movement, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) has partnered with Middle East Images to present a powerful collection of photographs that highlight the courage of the protesters who faced down the Islamic Republic’s security forces and the brave photographers who documented their resistance.

These photographs were taken by photojournalists who have faced state violence and detention for exposing the unwavering courage of Iran’s peaceful rights movement and the brutality of the Islamic Republic’s violent crackdown on protesters.

Despite their work being published by various media outlets, they must remain anonymous for their safety, as Iran is among the most repressive countries for journalists and artists. However, the following interviews provide a rare and invaluable insight into their experiences.

“The Islamic Republic seeks to conceal its atrocities and crimes against humanity from the world. Yet, courageous photographers, journalists, and activists risk their lives to expose these brutal acts, standing defiantly against the Iranian authorities’ oppressive rule,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of CHRI.

Two years ago, on September 16, 2022, 22-year-old Mahsa Jina Amini was killed in state custody days after her arrest for allegedly “violating” mandatory hijab laws. Her death ignited the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests across Iran. In response, authorities launched a brutal crackdown, killing over 500 protesters. Hundreds were intentionally blinded, tens of thousands were arbitrarily arrested, women and children were tortured, and ten protesters were executed.

As we commemorate the second anniversary of Iran’s “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, it is crucial to emphasize that not one official has been held accountable for the atrocities committed by state forces against the protesters. The UN’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Islamic Republic of Iran (FFMI) has documented that these atrocities rose to the level of crimes against humanity. CHRI echoes the FFMI’s recommendation for states to employ universal jurisdiction to prosecute the Islamic Republic officials responsible for these crimes.

“Despite enduring a brutal crackdown, the bravery of Iran’s Woman, Life, Freedom movement remains steadfast. Women and men, especially the youth, continue to stand up to a repressive government through daily acts of peaceful resistance despite threats of torture, execution, and imprisonment. Their resilience deserves the world’s full support,” Ghaemi added.

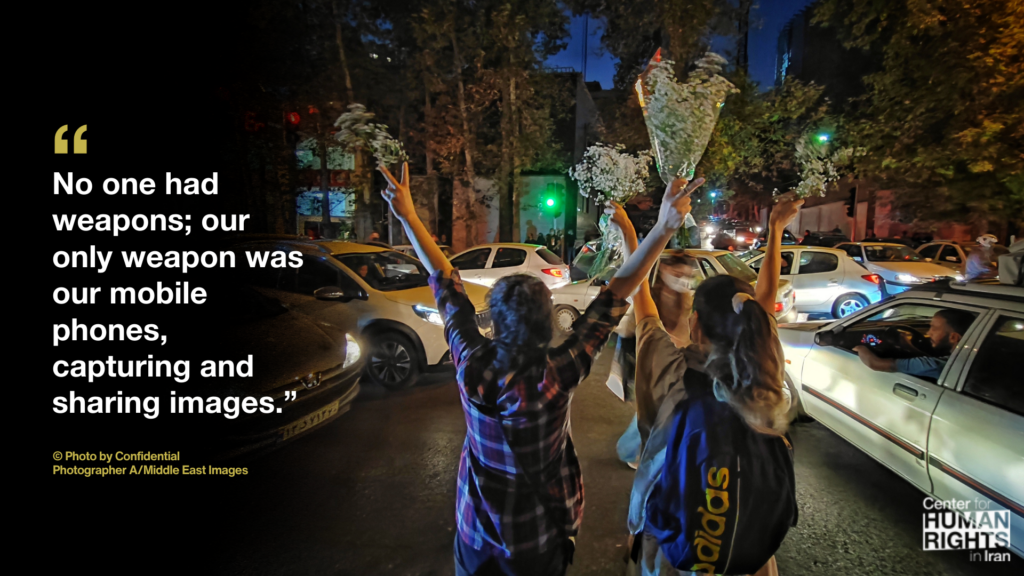

© Photo by Confidential Photographer A/Middle East Images

Photographer A:

“When I wanted to take photos or document the events, I would sometimes record videos and send them, but I couldn’t keep them because it was such a terrifying atmosphere. Once they were shared, I would delete them.

“We had put some lemons in our bags to pass around so that when tear gas was fired, people could squeeze them into their eyes to neutralize the effect. In my own bag, I had also put goggles in case they shot at us with rubber bullets so that they wouldn’t hit my eyes. We had prepared ourselves like this to go out.

“No one had weapons; our only weapon was our mobile phones, capturing and sharing images.”

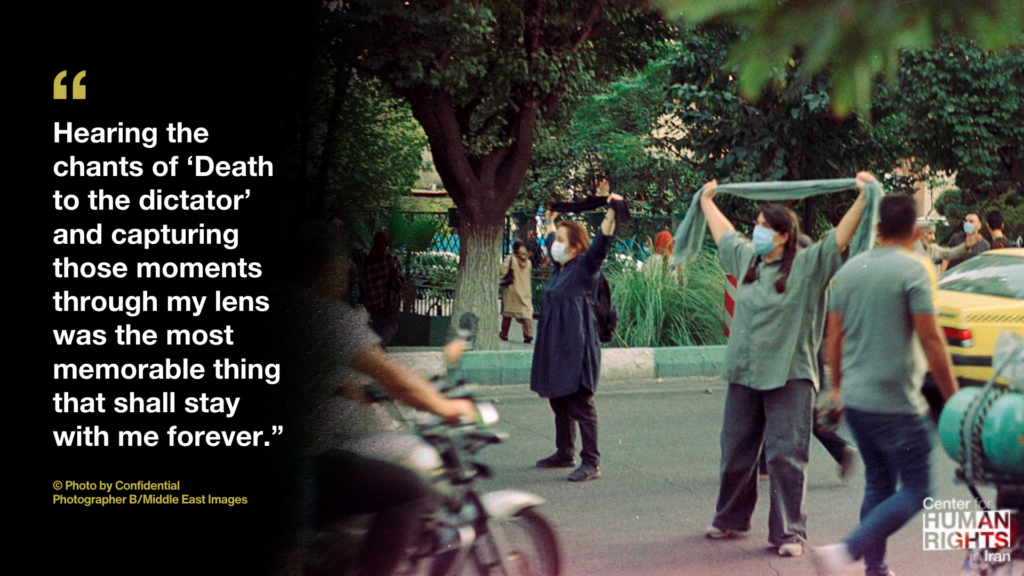

© Photo by Confidential Photographer B/Middle East Images

Photographer B:

“During the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, I took to the streets of Tehran as both a protester and a photographer. My time there only lasted for the first five days, but during that short period, I managed to capture two rolls of film. From the very beginning, the protests were met with the regime’s usual brutality. It was unrestrained, raw violence with a single aim—to scatter and silence any voice that opposed the government.

“Hearing the chants of “Death to the dictator” and capturing those moments through my lens was the most memorable thing that shall stay with me forever.

“Tear gas, baton-wielding police, and the deafening roar of motorbikes became inseparable elements of the protests. One of the most surreal moments was when strangers would blow cigarette smoke into each other’s faces to neutralize the effects of the tear gas—it felt like giving someone their breath back.

“The moment of my arrest was one of pure surrender. At 7 a.m., they stormed my workplace, arresting me. Shortly after, they raided my home, seizing my cameras and equipment. Hours later, I found myself in prison, being interrogated.

“The worst moment of the protests was hearing the sickening sound of a young man’s face being crushed under the blows of two plainclothes officers. They hit him with the butt of a rifle—completely unnecessary, probably done out of sheer enjoyment.

“The best moment of the protests was when we, with nothing but our bare bodies, drove a large group of motorcyclists back. Our bodies were the only weapons we had, but together, we made them retreat.

“I was arrested on the fifth day of the protests and spent fifty days in prison. Six months after my release, I managed to leave Iran. The memories of prison and what my family and I endured are too vast to capture here. But those fifty days were a daily battle—to keep from losing hope, to keep going, to hold onto the reasons we took to the streets in the first place. It was a struggle to protect my comrades, to not give away any names, to hold on to my spirit, and to keep the hatred for our real enemy alive.

“I believe the Woman, Life, Freedom movement accomplished two things. First, it awakened a sense of justice in a generation that had never had the chance to express itself. Second, it exposed those who claimed to oppose the Islamic Republic but couldn’t organize a resistance force for even a few months. It also shifted the mindset of the older generations, revealing the true face of the regime to the more religious sectors of society. As one friend put it, if seeing a 12-year-old child shot in the head with a military weapon doesn’t awaken your conscience, then nothing else will.”

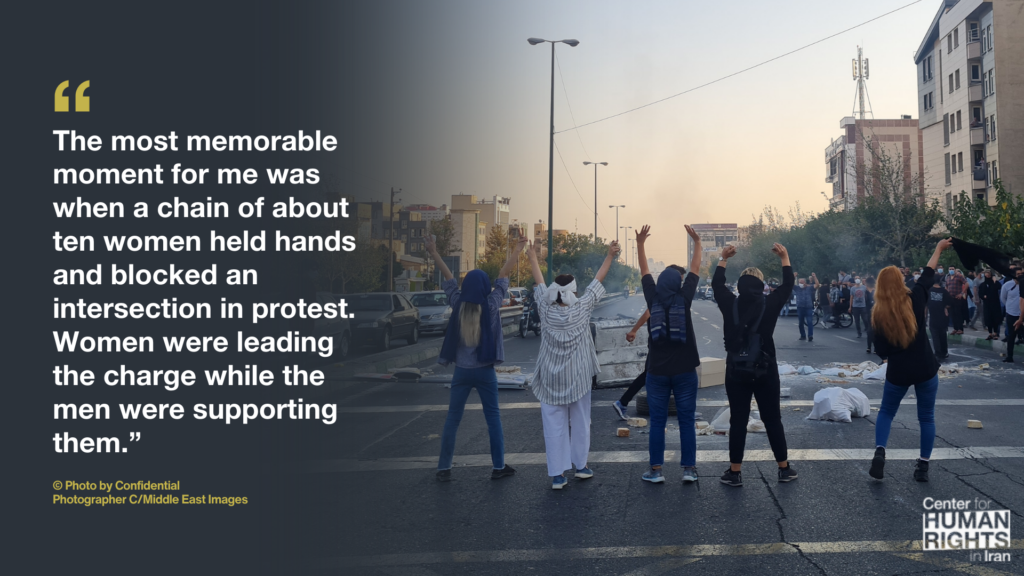

Photographer C:

“The most memorable moment for me was when a chain of about ten women, most of whom were over thirty, held hands and blocked an intersection in protest. It was a powerful image, and it struck me deeply that, this time, women were leading the charge while the men were supporting them. That was truly the most beautiful moment of all the events for me.

“On the other hand, my worst experience was after three months when one of my close friends was released from Evin Prison. I witnessed firsthand the physical and mental scars they bore. They would wake up in the night in terror, screaming, unable to find peace. It was heartbreaking to see the pride and bravery from before overshadowed by the trauma and suffering we were left to deal with. In the end, the aftermath of those days was more painful for me.”

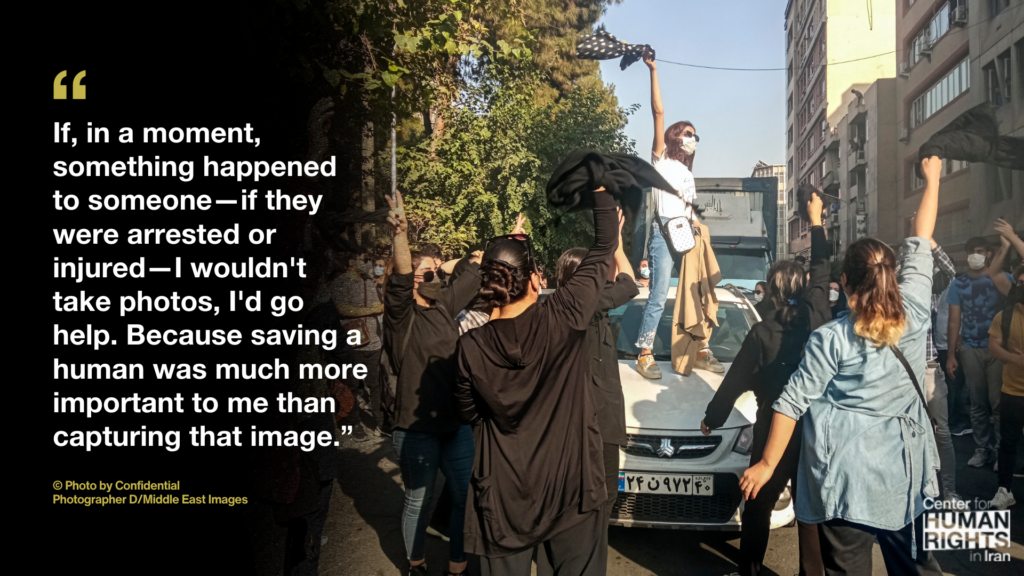

Photographer D:

“The first thing I could do on all the days I was at the protests was to help and stand by the people, and then take photos. That means if, in a moment, something happened to someone—if they were arrested or injured—I wouldn’t take photos, I’d go help because saving a human was much more important to me than capturing that image. Yes, I am a photographer, and I was supposed to capture it, but I feel like saving that person had a far greater impact on my life than taking that photo. No matter what would happen with the photo, even if it became famous or won awards. But at that moment, saving a life was much more important to me.

“After I was released, a significant event was that I saw many girls freely wearing what they wanted and being in the streets as the protests continued. It was good to see that people were not regretting their actions, despite the harsh sentences given to them. Everyone who had been in prison and was later freed remained resolute, and their courage was inspiring. However, a personal downside was feeling much more isolated compared to before. I found it challenging to find work, return to my previous job, or resume photography, as I was unable to pick up the camera again.

“What my interrogator told me was, “We will make you regret this so that you can’t work anywhere or establish any connections.” I don’t know if this was all planned or if they had predicted it, but everything they said came true. I experienced severe depression for a while, and on top of that, due to the illness I had and the medications I was taking, my body had become very weak. A new illness had also appeared, and unfortunately, two of the femur bones in my pelvis had turned black. I needed surgery as soon as possible, but I had no income and no financial support, which made it very difficult for me. Despite all this, I remained determined to resume photography, to return to the streets, to show the realities of society, and to continue fighting against this regime.

“But I lived for survival, I lived for victory, and I lived to show that victory. Even now, I still have that hope, and I’m certain we will achieve it. I am doing everything I can to be there on the day, the day of victory, when I can capture that photo because it is our right. We, the people, have the right to be free. We have the right to think about victory in our fight against this regime, and I hope that day comes soon.

“Those who have fallen into the trap of this Islamic Republic and ended up in prison, we have seen the end of the Islamic Republic. The end of the Islamic Republic is either to throw you in prison, kill you, or prevent you from working and put pressure on your family. Everyone who has been imprisoned or arrested has seen all this.”

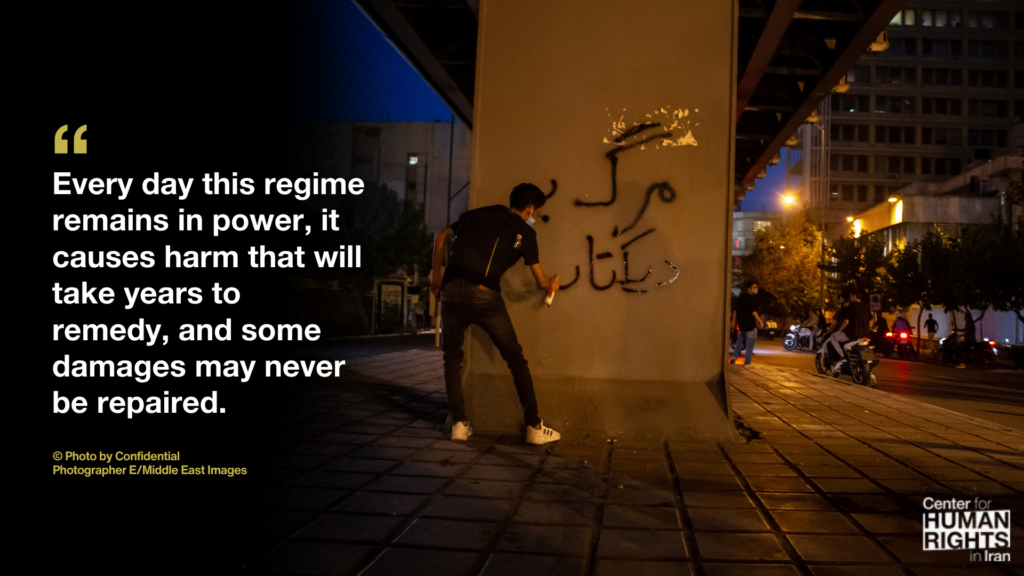

© Photo by Confidential Photographer E/Middle East Images

Photographer E:

“When the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ protests began, I noticed that many experienced journalists and photographers had been detained and were now confined to their homes. This motivated me to take my own camera and start photographing, despite my inexperience in documentary photography. I tried to overcome my fear and capture everything I saw.

“During the protests, like everyone else who participated, I came close to being arrested several times. I was directly hit by a tear gas canister once, and when the smoke cleared, I couldn’t see anything. A few people helped me, and we went into a house where I took a photo of a young man receiving first aid from a woman. On the day of Nika’s memorial, I was hit by a pellet in the face.

“After the protests, facing the reality of continuing under the oppressive regime, despite all the fighting, deaths, and the blinding of my fellow citizens, was a profound grief that still affects me. It wasn’t just me; many in our community felt hopeless and fell into depression. Over time, we tried to pull ourselves together because that hopelessness is what the regime aims for—to create a depressed society that cannot make decisions or take action.

“I knew I had to keep going. I believe we can’t just sit idly by. Every day this regime remains in power, it causes harm that will take years to remedy, and some damages may never be repaired. Nevertheless, everyone must resist injustice in their own way. My tools are photography, filmmaking, and writing. Even after the protests, I haven’t stopped. I continue to take photos, make films, and write.”

This report was made possible from donations by readers like you. Help us continue our mission by making a tax-deductible donation.