House Arrest of Presidential Candidates, Long a Taboo Topic, Emerges as Public Issue Again in Iran

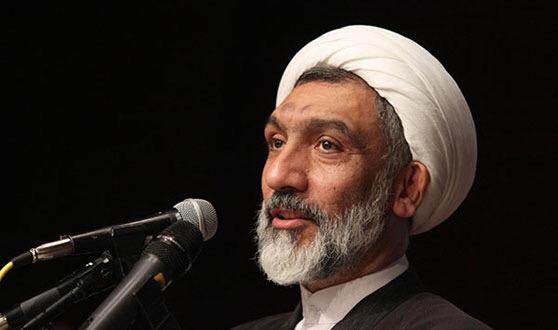

Three days after President Hassan Rouhani suggested the possibility of a legal solution to the long-running house arrest of Iran’s former presidential candidates, his Minister of Justice, Mostafa Pourmohammadi, said the house arrests were a product of security issues during an earlier period of unrest and that now could be the time to revisit the issue.

“Now is the opportunity to reconsider the house arrests [but] the President does not believe the conditions are suitable today to bring up this issue and decide on it,” Pourmohammadi was quoted as saying at a press conference on September 1, 2015.

Hours later, the Justice Minister’s controversial comments were removed from news websites in Iran, indicating just how sensitive the issue of the house arrest remains for authorities, but the next day some agencies published it.

Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, presidential candidates in the 2009 election, and Zahra Rahnavard, Mousavi’s wife, have been under house arrest, without charge, since February 2011 for disputing the validity of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s victory and urging protests months after the election.

The three became leaders of the Green Movement, which arose from the widespread peaceful protests that broke out across Iran in 2009 over the results of that election. The protests were violently suppressed by the state. The media have been instructed not to raise the issue of the house arrests, and the 2009 protests continue to be referred to as the “Sedition” by authorities in Iran.

“The house-arrest issue may be legally indefensible. But we must accept that this was a security issue particular to its time,” Pourmohammadi said, adding that the house arrests, originally decided by the National Security Council, could not be ended by the government or the courts.

When asked by a reporter about the issue of the house arrests on August 29, 2015, President Rouhani compared it to an “unripe fruit” that the government could not touch. But he also suggested that it should not drag on indefinitely. “No matter who was right or wrong, it should not become a permanent problem,” he said. “I have said it before: there are some issues the government cannot do anything about on its own. But the government can prepare the grounds.”

In another indication of the continued sensitivity of the house arrest issue, the leader of the newly-formed reformist Iranian National Union Party, Ali Shakouri-Rad, was briefly arrested on August 31, 2015, hours after a press conference where he called for a resolution to the house arrests. “We regret that the house arrests remain a sore wound that hasn’t healed since 2009,” he said. Shakouri-Rad’s arrest reflects the extent to which the house arrests are still somewhat of a taboo issue.

During Rouhani’s presidential campaign, he raised the issue of the house arrests of Mousavi, Karroubi and Rahnavard. On May 13, 2013, Rouhani told students at Sharif University that perhaps in a year conditions would be right to end not only the house arrests, but to release all who were arrested in connection with post-election unrests of 2009. He stated, “If I am president, I believe that this rift is not in our best interest….the future administration must create a non-security state. We can provide conditions such that over the next year, individuals who were imprisoned or put under house arrest for the 2009 events are released. And on June 8, 2013, Rouhani said “Why political prisoners? We must do something for all these prisoners to be released”.

However, since Rouhani’s election two years ago, statements of support for the Green Movement leaders have been few and far between, and the three continue to languish under house arrest.