Imprisoned Editor Hospitalized After 18-Day Hunger Strike

Open Letter Disproves Judicial Claim About Prisoners’ Rights

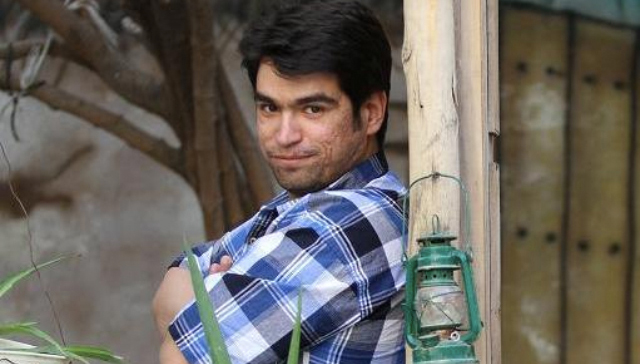

Imprisoned newspaper editor Ehsan Mazandarani, who recently wrote an open letter disproving a judicial official’s claim about prisoners’ rights, was rushed from Evin Prison to a hospital outside the prison on October 9, 2016 following an 18-day hunger strike.

“My client is eligible for conditional release because he has served almost half of his prison term and now that he has been hospitalized, he should be granted his release so he can take care of his medical issues,” Mazandarani’s lawyer, Houshang Pourbabaei, told the semi-official Iranian Student News Agency (ISNA).

According to Article 58 of Iran’s New Islamic Penal Code, the deciding court can grant conditional early release to prisoners sentenced to less than ten years after they serve a third of their term.

Mazandarani’s wife, Maliheh Hosseini, meanwhile said in an interview with the semi-official Iranian Labor News Agency (ILNA) that she had been informed that the prison doctor at Evin Prison “expressed concern about Ehsan’s condition, and said he was not able to do anything for him.”

Hosseini added that Mazandarani, the editor-in-chief of the reformist Farhikhtegan newspaper, was suffering from a bleeding stomach and extremely low blood pressure. Mazandarani, who has been imprisoned since his arrest on November 2, 2015, was also previously hospitalized after a 14-day hunger strike on May 31, 2016.

Open Letter

Seven days before his most recent hospitalization Mazandarani had disproved claims by a judicial official that national security suspects can exercise their right to legal counsel.

In a letter published on October 2, 2016 in ILNA, Mazandarani refuted Judiciary Spokesman Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei’s recent comment implying that suspects charged with national security crimes could access legal counsel throughout their detention in Iran.

“All cases concerning national security suspects proceed in the presence of defense lawyers who are able to study the charges,” Ejei told reporters on September 18, 2016. “How can a lawyer not be involved in presenting a defense?”

In his letter, Mazandarani wrote: “After I was detained by the Revolutionary Guards’ Intelligence Organization on November 2, 2015, I was questioned the next day and explicitly told by the interrogator, Mr. Abolfazl Hassanzadeh, that I do not have the right to a lawyer unless the chief of the Judiciary approves his or her qualification.”

Mazandarani added that since his arrest, he has had just one meeting with a member of his defense team, attorney Mahmoud Alizadeh Tabatabaee, and that the meeting lasted three minutes before the start of the preliminary trial on April 26, 2016 at Branch 28 of the Revolutionary Court. That day Mazandarani was sentenced to seven years in prison for “assembly and collusion against national security” and “propaganda against the state” by the court. Three months later the Appeals Court reduced his sentence to two years in prison.

Article 35 of Iran’s Constitution guarantees prisoners the right to legal counsel. According to Article 48 of Iran’s Criminal Procedure Code, “Once a suspect comes under criminal supervision, he or she can seek the presence of lawyer.”

However, according to an amendment to Article 48: “During preliminary investigations involving national security crimes inside or outside of the country… suspects can choose a lawyer or lawyers from the Bar Association who are approved by the Judiciary.”

Speaking to the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran in June 2015, legal expert Masoud Shafie, a member of Iran’s Bar Association, said the amendment is unconstitutional: “It contradicts Article 35 of the Constitution, which clearly states that any person can have a lawyer and no one can prevent their access to a lawyer.”