Tehran Prosecutor Calls Hunger Strikes “Threats” Amid Mass Strike at Rajaee Shahr Prison

“Prisoners must endure their punishment to the fullest”

“Prisoners must endure their punishment to the fullest”

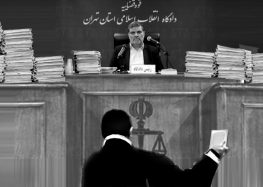

Tehran Prosecutor Abbas Jafari Dowlatabadi has described hungers strikes undertaken by prisoners as “threats” that the judicial system will not “surrender to.”

Dowlatabadi made the comments as more than a dozen political prisoners entered the third week of a mass hunger strike at Rajaee Shahr Prison in Karaj.

“To those prisoners who resort to hunger strikes and other actions, we say these methods have been defeated,” said Dowlatabadi on August 23, 2017, at a conference in Tehran focused on reducing Iran’s prison population. “The judicial system will not surrender to their threats.”

“Prisoners must endure their punishment to the fullest,” he added. “We will not be influenced by the prisoners’ actions, such as hunger strikes.”

The Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) has learned from interviews with relatives of Rajaee Shahr hunger strikers that their number has grown to at least 18 since the protest began on July 30, 2017. That day more than 50 political prisoners and prisoners of conscience were suddenly transferred from Ward 12 to Ward 10.

Ward 10, located on the third floor of the prison compound, has been equipped with enhanced security gear such as closed-circuit cameras, microphones and jamming devices to block smuggled mobile phones.

The hunger strikers have been demanding the return of personal effects, including clothes, medications and electronic equipment that they weren’t allowed to take with them when they were transferred. They are also protesting the ward’s poor ventilation and enhanced security.

“The prison medical staff have not checked the conditions of the prisoners even though close to 20 of them are on hunger strike and five or six, who started the protest first, are not feeling well,” one of the hunger strikers’ relatives told CHRI on condition of anonymity.

Those in poorest health include Saeed Masouri, Mohammad Banazadeh, Amir Khizi and Reza Akbari Monfared, who have been on a wet hunger strike, ingesting only salt water and other liquids such as milk, added the source.

“During family visitation at the prison today [August 23], we found out that other than returning only some of the prisoners’ medications, nothing much has been done,” said the informed source. “The authorities say they will only return things like television sets, refrigerators, kitchen equipment and rugs to the prisoners’ families, but it seems like there’s a general looting going on.”

“There’s still the problem of ventilation, made worse under the summer heat and the existence of all the closed-circuit cameras and listening devices,” added the source.

The source also told CHRI that some of the prisoners’ relatives attempted to deliver a letter to the authorities at Rajaee Shahr Prison, but were turned away: “We tried to deliver a letter but the head of security insulted us and pushed one of the mothers down the stairs.”

According to the letter, a copy of which was obtained by CHRI, “On Sunday, July 30, [2017], without prior notice, prisoners in Ward 12 were handcuffed, and some dragged and beaten, while being transferred in a humiliating and inhumane manner to a new ward that lacks any kind of basic facilities, without being allowed to carry along their personal belongings, or even necessary medications.”

“This latest action against prisoners’ human rights is a violation of the State Prisons Organization’s regulations, and unfortunately the authorities’ lack of response to repeated written and verbal complaints has led the prisoners to start a mass hunger strike,” added the lettter. “The worsening condition of the protesting prisoners and lack of medical attention are increasingly worrying for the families.”

Article 161 of the State Prisons Organization’s Regulations bans “mass protests and strikes by prisoners.” However, the current situation in Rajaee Shahr Prison’s Ward 10 was created by the authorities’ violation of Article 37, which states that prison authorities “must exercise sufficient care and attention in the safe return of convicts’ personal effects at the time of their release or during transfers.”

The sudden transfer and the initial denial of prisoners’ visitation rights were also illegal, according to a prominent Iranian human rights attorney.

“It is against our prison regulations and international laws to move prisoners without their knowledge or informing their relatives,” Mohammad Seifzadeh, who spent five years in Rajaee Shahr Prison and spoke out about the prison’s conditions after his release, told CHRI.

Article 50 of Iran’s prison regulations calls for transparency in detention centers by requiring the authorities to allow prisoners to inform their relatives of where they are being held “by telephone or any means possible.”