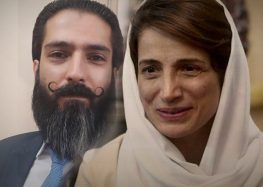

Hundreds of Iranian Rights Activists Call on Political Prisoner Mohammad Nazari to End Hunger Strike

Mohammad Nazari has been imprisoned since 1994.

More than 700 Iranian political and civil rights activists have called on one of Iran’s longest serving political prisoners to end his life-threatening hunger strike.

In an open letter sent to the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) on October 24, 2017, the political and civil rights activists expressed concern over Nazari’s deteriorating health and assured him, “your voice has been heard by Iranian civil society.”

“Mohammad Nazari is seeking a judicial review of his sentence, based on the latest Islamic Penal Code ratified in 2013,” said the letter. “Applied retroactively, Nazari’s life sentence would change to 15 years in prison. But the judiciary is stubbornly refusing to carry out the law, forcing Nazari to fight to the death for his rights.”

“The judiciary is so insistent on breaking the law that political prisoners and prisoners of conscience have to put their lives on the line by going on hunger strikes to seek the implementation of the most obvious of laws,” the activists wrote in their letter. “As we know, these hunger strikes leave a heavy toll, leaving prisoners suffering from the impact for years.”

A 45-year-old ethnic Azeri Turk, Mohammad Nazari has been imprisoned since 1994. Eligible for release, he is serving a life sentence in Rajaee Shahr Prison, known for its inhumane conditions, for his alleged membership in an outlawed Kurdish separatist organization.

A source inside the prison told CHRI on October 25 that Nazari was rushed to a hospital outside the facility last week after a severe drop in blood pressure, but was returned to his cell hours later after a brief medical check-up.

Nazari began his hunger strike on July 30, 2017, and is taking minimal liquids and small amounts of food to sustain him long enough for the judiciary to review his case.

Since his arrest on May 30, 1994, by agents of Iran’s Intelligence Ministry in the city of Boukan, West Azerbaijan Province, Nazari has not been granted furlough. The temporary leave, which is typically granted to non-political prisoners in Iran for a variety of familial, holiday, and medical reasons, is routinely denied to political prisoners as a form of additional punishment.

Nazari’s parents and brother died while he was incarcerated, meaning he has no one to follow up on his case, and he does not have access to legal counsel.

In November 1994, Branch One of the Orumiyeh Revolutionary Court sentenced Nazari to death for his alleged membership in the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI), an opposition group seeking autonomy for the mainly-Kurdish populated region of northwestern Iran.

In an open letter from prison dated October 18, 2017, Nazari said he was eligible for release based on articles 10, 99, 120 and 728 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code.

“If the law had been applied, I would have been freed four and a half years ago,” he wrote. “But invisible hands rooted in centers of power and the security establishment are preventing the implementation of the law in my case.”

“Don’t abandon me,” pleaded Nazari in his letter. “I don’t have anyone. My father, mother and brother were laid to rest years ago in the cemetery in Boukan. Your helping hand is my only hope. Help me. Help me so that my voice can be heard. Help me gain the freedom I am legally entitled to.”

Article 10 of the Islamic Penal Code stipulates, “… [I]f, after the offense is committed, a law is passed that provides mitigation or abolition of the punishment or security and correctional measures, or is favorable to the perpetrator in some other way, it is applicable to the offenses committed prior to the passage of the law until the final judgment is issued.”