Initial Reports Show Thousands Arrested in Iran’s Crackdown on November Protests

*This article was updated with additional details on November 25.

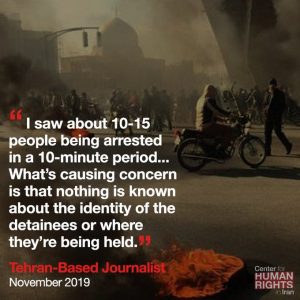

Early Tally Indicates at Least 4,000 Arrests as Concerns Mount for Detainees Smeared by State Media as “Rioters”

In the wake of preliminary reports suggesting that thousands of people were arrested in the Iranian government’s crackdown on mass protests that broke out across the country in November 2019, there are grave concerns that detainees are being denied due process while state officials smear them as “rioters” and “saboteurs.”

Eight days after protests erupted across dozens of Iranian cities following a gasoline price hike announcement, no Iranian official has provided a credible current estimate of the total number of people who’ve been arrested so far.

As of November 22, initial figures that the Center for Human Rights in Iran’s (CHRI) was able to collect from officials cited in state media reports and individuals inside Iran indicated 2,755 individuals were arrested, but multiple sources involved in gathering information about the arrests throughout Iran told CHRI that their estimates surpassed 4000 arrests and were growing daily.

In many cities, because of the internet shut down in the country, news blackout and officials’ refusal to share information about the arrests, the number of arrests has not been reported. Given the protests in many cities and the reports confirming the use of state violence and mass arrests, it’s expected that the overall number will grow. Many observers believe the actual numbers may well be significantly higher.

On November 19, Amnesty International, citing “credible reports,” stated that at least 106 people had died in the protests, which state security forces violently repressed according to reports by eyewitnesses as well as video and pictures shared on social media networks.

On November 19, Amnesty International, citing “credible reports,” stated that at least 106 people had died in the protests, which state security forces violently repressed according to reports by eyewitnesses as well as video and pictures shared on social media networks.

Sources with detailed knowledge about what is happening inside Iranian prisons have meanwhile informed CHRI that prison authorities relocated existing prisoners to make room for the sudden influx of new detainees.

“Many prisoners held in cells under the control of the Intelligence Ministry and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps have suddenly been moved to public wards in order to make room for the new detainees,” one source told CHRI.

All the sources that spoke to CHRI for this report did so on the condition of anonymity to protect their personal security.

CHRI is deeply concerned about reports that detainees are being denied contact with their relatives who are struggling to locate them, as well as by state-funded media outlets advocating punishments for detainees who’ve not yet been tried with the right to fully defend themselves.

A commentary published in the ultra-conservative Kayhan newspaper, which presents itself as an unofficial mouthpiece for the supreme leader, suggested that detained protesters could be executed.

“Some reports indicate that judicial authorities are certain that the leaders of the recent riots will be punished by execution through hanging,” said the November 18 unsigned commentary. “Crimes committed by rioters amount to ‘rebellion’ and their punishment under the law and Sharia is execution.”

Numerous international rights organizations and foreign governments have condemned the Iranian government’s violent repression of the protests.

On November 22, the UN called on Iranian authorities to “ensure that the rights to freedom of opinion and expression, as well as freedom of peaceful assembly and association, are respected and protected.”

That day, the German foreign ministry had called on “Iranian security forces to exercise the greatest possible restraint.”

A day earlier, on November 21, the European Union’s External Action Committee had called on Iran’s security forces to exercise “maximum restraint” in handling the protests, adding that “any violence is unacceptable.”

State Media Outlets Smear Detainees as Iran Begins Creeping Out of Internet Blockade

As of November 22, 2019, access to the international internet in Iran was at 15 percent of normal levels, according to the internet-governance-focused NetBlocks organization.

The Iranian government had imposed an internet blackout from November 16 until 21, when it began to lift the blockade in some cities. People in Iran were allowed access to the state-controlled, heavily filtered and censored “national internet” during that time.

As of November 21, the Iranian government had also blocked access to the app stores of the Android and iPhone mobile phones, leaving millions of users in the country open to a range of security risks and with phones that can only operate state-approved apps, according to CHRI’s investigations.

The internet blockade has been widely condemned by international rights organizations.

On November 22, the UN urged the Iranian government to “restore full internet access and commit to keeping the internet up and running at all times, especially during times of public protest.”

As more Iranians gain access to independent news reports through the less censored internet access that is currently being restored, officials are stepping up attempts to smear the citizens who joined the protests.

Families are meanwhile struggling to locate loved ones who were detained in the state’s crackdown. According to Iran’s Criminal Procedures Code, the authorities are legally obligated to allow detainees to have contact with their families. But many families have been turned away by the authorities, while their loved ones have been denied phone access.

An informed source in Tabriz, East Azerbaijan Province, told CHRI on November 21 that concerned family members of detained protesters held in the city’s local detention center run by the Intelligence Ministry were told that information would be given by judicial officials “when necessary.”

In Shiraz, Fars Province, detained protesters were being held in the quarantine section at Adelabad Prison, according to an informed source, who added that none had been allowed to contact their families.

On November 22, the Evin Public Prosecutor’s Office announced that relatives should not come to Evin Prison looking for anyone for at least two more weeks.

State TV has meanwhile been airing reports that vilify the detainees in the eyes of the public before they’ve been tried in a court of law.

On November 20, the state-controlled Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) aired alleged “confessions” by a woman of Kurdish descent from the city of Boukan in northwest Iran, named by the broadcaster as Fatemeh Davand, calling her “one of the main instigators” of protests in the city. IRIB also claimed she was arrested while attempting to escape the country.

IRIB has a documented history of working with security and intelligence officials to extract false “confessions” from detainees held on politically motivated charges. The confessions are often elicited under physical and/or psychological torture and then aired on state TV in order to discredit detainees before the public and convict them.

On November 22, the IRIB’s local branch in the city of Isfahan aired alleged “confessions” by three “rioters” who the broadcaster claimed attacked people with machetes and destroyed public property.

Similar broadcasts were aired by the IRIB’s local branch in Shiraz on November 19.

In early November, Parliament was presented with a bill that would make recording forced statements by detainees and airing them on state TV illegal, but the bill appears stalled in the preliminary stages.

Students, Former Prisoners of Conscience Among Thousands Arrested in Crackdown

As in the cases of previous large-scale state crackdowns, the number of people who were arrested in Iran’s November 2019 protests can only be estimated based on official statements and reports provided by sources with detailed knowledge of state figures, detention centers, and reports by detainees’ relatives.

In some cases, it’s unclear whether large numbers cited by officials include earlier reports or should be added to existing reports. While Iranian officials often claim arrest figures are inflated, reports by detainees, their relatives, and activists indicate that the numbers are actually underreported.

Early numbers cited by these sources indicate that a range of people from ordinary citizens, to activists, to university students, to ethnic minorities were arrested during the November 2019 protests.

When citing numbers, most officials refer to the protesters as “rioters” or “saboteurs,” and in some cases claimed they were not Iranian citizens. Following is a listing of some of those reports.

On November 18, a group of students at the University of Tehran was arrested and taken to an unnamed prison, according to an independent news channel belonging to the Iranian Students Trade Union Council on the Telegram messaging app.

“Students held a gathering to protest the three-fold increase in the price of gasoline, deplorable living conditions and heavy-handed oppression,” said the report. “The protest began on Monday evening [November 18] and lasted until 8 at night. As darkness approached, several ambulances carrying plainclothes agents entered the campus, arrested several students and took them away in ambulances.”

Some of the detainees, numbering “40 to 50” students, were taken to Tehran’s Evin Prison while others were transported to the Greater Tehran Central Penitentiary (GTCP) in the city of Fashafouyeh, 20 miles south of the capital, according to the report.

“The security agencies have warned many students and their families that they would be arrested if they were seen [protesting] on campus,” the report said.

On November 21, university student activist Yashar Darolshafa was detained, according to his relative, who told the student union that Darolshafa is in poor health and suffering from severe back and leg pain.

Other student activists arrested between November 18-21 include Hassan Khalifehie, Kamyar Zoghi, Ali Nanvaie, Melika Gharehghozlou, Marjan Eshaghi, Maliheh Jafari, Marjam Jafari, Nadia Gholami, Amir Forsati, Narges Bagheri and Saha Mortezaei, according to the student union’s report.

Deputy Science Minister Gholamreza Ghaffari and University of Tehran Chancellor Mahmoud Nili Ahmadabadi denied having knowledge of the arrests. Then on November 21, Esmail Soleimani, the head of security at the University of Tehran, said the number of arrested students had been “exaggerated.”

“A small number of students were arrested at the University of Tehran and at Allameh Tabataba’i University,” he told the state-funded Iranian Labor News Agency.

On November 16, former prisoner of conscience Sepideh Qoliyan, who had been free on bail pending a decision on her appeal against a 18.6-year prison sentence since October 26, was re-arrested for allegedly “participating in protests against the increase in the price of gasoline” in Dezful, Khuzestan Province, according to a local state media outlet report.

On November 17, in the city of Shahriar, Tehran Province, the city’s governor Nourollah Taheri said about 80 protesters, allegedly “mostly non-natives,” had been arrested.

On November 18, Fars News, which is affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), reported that “about 1,000” had been arrested throughout the country since November 16.

On November 18, Fars News, which is affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), reported that “about 1,000” had been arrested throughout the country since November 16.

Fars News reported on November 19 that seven individuals had been arrested after allegedly setting fire to five banks in south Tehran and that they “were citizens of an eastern neighboring country.”

That same day in Khuzestan Province, Governor General Gholamreza Shariati claimed that between November 16-19, 180 people had been arrested. Local human rights activist Karim Deyhimi told CHRI that the actual figure was closer to 400.

On November 19, the IRGC’s intelligence organization in Fars and Alborz provinces announced the arrests of 100 and 150 “riot leaders” respectively. Those arrested in Alborz Province included “dual nationals” with passports from Germany, Turkey and Afghanistan, alleged the organization.

On November 20, Ahmad Nourian, the spokesman for Tehran’s police, said “a considerable number of rioters and saboteurs” had been arrested but did not provide an exact figure.

That same day, Mohammad Mousavi, the military governor of Gachsaran, Khuzestan Province, said 150 people had been arrested in the city as of November 20.

Other arrests reported by official sources include:

— 34 in Robat Karim, Tehran Province,

— 30 in Boumehen and Pardis, Tehran Province

— 29 in Birjand, Southern Khorasan Province

— 5 in Islamabad Gharb, Kermanshah Province

— 30 in Zanjan, Zanjan Province

— 25 in Islamshahr, Tehran Province

— 40 in Yazd, Yazd Province

— 30 in Tabriz, East Azerbaijan Province

— 35 in Baharestan, Isfahan Province

An informed source based in northwestern Iran told CHRI that as of November 21, some 20 protesters had been arrested in the cities of Javanroud, 42 in Marivan, 112 in Boukan, 51 in Sanandaj, and 39 in Kermanshah. The numbers could be much higher, according to the source.

In addition, an unidentified administrator of an unnamed Telegram channel “with 23,000” followers was arrested in Babol, Mazandaran Province, on November 21, according to the state-funded Mashregh News.

On November 21, Fars News claimed that one of the people arrested for allegedly blocking the Imam Ali Highway in Tehran “was a retired employee of the Danish embassy” and a search of his home had led to the discovery of “a handgun with bullets, a spy camera and a number of electronic equipment.”

Arrest numbers have also been cited by Friday prayer leaders who have also smeared the protesters before they’ve been tried in courts of law.

Ahmad Alamolhoda, the Friday prayer leader of Mashhad, said on November 22 that “400 rioters were arrested in Mashhad but 90 percent of them were inexperienced young people who were released the same night.”

That same day, judiciary spokesman Gholam-Hossein Esmaili said that “the IRGC alone gave up a report that about 100 leaders, heads and primary agents of the riots in different parts of the country were identified and arrested. A much larger number have been identified by the Intelligence Ministry. Some of them have been arrested and others are about to be arrested.”

Read a version of this article in Persian.