Detained Pro-Rouhani Telegram Channel Admins Repeatedly Denied Legal Counsel Three Months After Arrests

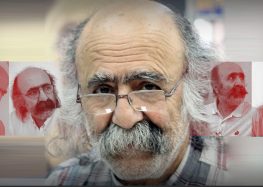

Mohammad Taher Kanani, the lawyer representing Nima Keshvari, a Telegram channel admin who was detained in March 2017.

More than one hundred days after a group of social media supporters of President Hassan Rouhani were arrested by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the detainees are still being denied access to legal counsel, according to one of their lawyers.

“I went to Evin Prison with a letter in my hand from the judge to sign a contract to represent my client Nima Keshvari,” Mohammad Taher Kanani told the Iranian Labor News Agency (ILNA) on July 2, 2017. “But I was not allowed to see my client and was told that I had to first become my client’s lawyer and then be able to see him.”

“But how can I become his lawyer without seeing him and signing a contract?” he added. “This is a violation of attorney-client privileges.”

Kanani was eventually allowed to read the contract over the phone to Keshvari, who signed it, but the IRGC agents in Evin Prison refused Kanani’s request for a face-to-face meeting with his client.

Ahead of the May 19 presidential election, Keshvari, Ali Ahmadnia, Mojtaba Bagheri, Sobhan Jafari-Tash, Javad Jamshidi, and Saeed Naghdi—all administrators of reformist news channels on the popular Telegram messaging network—were arrested between March 14 and 16.

Despite being denied legal assistance, some of the six have been charged and will soon face trial, according to the head of the Tehran Province prosecutor’s office, Alireza Esmaili, who made the comment to ILNA on July 5 without providing details.

Based on Article 48 of Iran’s Criminal Code of Procedure: “In the preliminary investigation stage of cases involving crimes against internal and external security, as well as organized crimes… both sides of the dispute can choose a lawyer or lawyers from a list approved by the judiciary chief.”

Pressured by concerned family and friends, on June 30 Keshvari ended an 11-day hunger strike to protest his prolonged detention while being denied access to a lawyer.

A few days earlier, Ali Mojtahedzadeh, an attorney representing two other detained Telegram admins, Javad Jamshidi and Sobhan Jafari-Tash, contradicted Judiciary Spokesman Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejei’s claim that the hunger strikes were merely a “rumor.”

“The esteemed deputy judiciary chief gave an interview yesterday and denied that the hunger strikes ever took place,” Mojtahedzadeh told ILNA on June 27. “Yet one of the detainees, Mr. Naghdi, has just broken his hunger strike and we don’t know how the others are doing.”

“The families of the detainees have asked me to help, but I have not been able to meet them,” he added. “The judiciary should explain why.”

Mojtahedzadeh previously told ILNA on June 21 that the arrests were the result of “political differences” between an unspecified party and the Rouhani government.

Attorney Mostafa Tork Hamadani said on June 21 that he had been denied a meeting with the detainees in Evin Prison.

“This is against the law. I will follow up this matter,” he said.

Heydar Valizadeh, another reformist channel admin on Telegram who is free on bail, criticized the government of President Hassan Rouhani for not doing enough to end his colleagues’ continuing detention.

“Unfortunately the government has not taken any serious steps other than serving us slogans despite the fact that all of them were staunch supporters of (Rouhani’s) government and spent years defending him in every capacity,” said a June 20 post on Valizadeh’s Telegram channel, which has since been deactivated.

In mid-March 2017, two months before Iranians voted in the presidential election, IRGC agents arrested a group of admins of 12 reformist-aligned Telegram channels, deleted the channels’ content and changed the names.

A month later, the judiciary accused Rouhani’s Intelligence Minister Mahmoud Alavi of colluding with the detained admins.

“Regarding this particular case, there are matters that relate to the intelligence minister himself,” said Ejei on April 12 while commenting on the case.

A photo had previously been shared on social media showing the minister posing with some of the detained admins.

Administrators of popular social media and online sites in Iran customarily meet with government officials as both sides try to win support and access.

“I don’t know of any crime the admins may have committed for which I share responsibility,” said Alavi in response to Ejei. “It looks like they may have been arrested because of me.”

On June 6, the families of five of the detainees went to Parliament and asked for an investigation into their loved ones’ cases.

Article 90 of the Constitution authorizes the legislature to investigate complaints from the public against all state branches and report their findings to the public.

“These arrests could be interpreted as the IRGC’s interference in the presidential election as a military institution, which is barred by the Constitution,” wrote reformist MP Mahmoud Sadeghi in an open letter to IRGC commander General Mohammad Ali Jafari on March 18, 2017.

On March 17, four reformist members of Parliament had demanded an explanation for the arrests from Rouhani.

“Foremost we expect your excellency to resolve this problem, but if no action is taken, we will invite the four ministers involved, namely the ministers of intelligence, justice, interior and Islamic guidance… to Parliament and pursue this matter until the truth becomes clear and the rights of the detainees are restored, even by impeaching the relevant ministers if need be,” said the letter signed by MPs Elias Hazrati, Abdolkarim Hosseinzadeh, Bahram Parsaie and Mohammad Ali Vakili.

Alavi answered the MPs’ questions in a closed parliamentary session on June 6. No details have been made public.

Rouhani, who called for an investigation into the arrests in late March, has followed up by criticizing the judiciary for making arbitrary arrests.

“We must have a reason if we summon someone,” he said at a national conference of judicial officials in Tehran on July 2. “We can’t summon someone and then find a reason. We need sufficient reason first. This is what our Constitution demands.”

“One of the president’s duties is to carry out the Constitution and helping the judiciary is part of that,” he added. “The president should be concerned with the judicial branch as much as the government and take action if he sees problems in the implementation of the law.”