Judicial Official’s Defense of Mass Executions Sets Dangerous Precedent

Senior Advisor to Judiciary Asks Why the State Should Be Concerned with “Legal Matters”

Pourmohammadi: “We still haven’t settled scores”

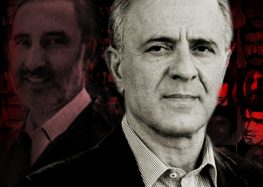

August 5, 2019—New remarks by a senior judicial official in Iran, Mostafa Pourmohammadi, in which he openly defended the extrajudicial executions of some 4000-5000 prisoners in 1988 as necessary acts against “enemies” in a time of war, mark a significant and dangerous turning point in the state’s treatment of those notorious mass killings, which have been internationally recognized as crimes against humanity.

The Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) forcefully condemns these remarks, which were made by an official who was himself one of the central figures responsible for those executions, and the depiction of the murder of thousands of prisoners, who had all been issued prison sentences and were serving their terms, as legitimate acts of war.

“The defense by a ranking judicial official of the 1988 mass executions is an attempt to legitimize state murder and the treatment of political opponents as enemy combatants, and reflects complete disregard for law and judicial process,” said Hadi Ghaemi, CHRI executive director.

In a videotaped interview with the hardline magazine, Mosalas on July 24, 2019, Pourmohammadi, who is now an advisor to Iranian Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi (who was also a central figure responsible for those executions), said: “During a war if we fire a mortar at the enemy and it lands next to them on a village, do we have answer questions about why the village was hit?” He added: “Are we expected to talk about legal matters, protecting citizens and human rights in the middle of a battlefield?”

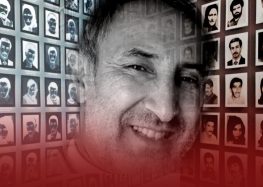

The 1988 executions were ordered by inquisition-like “death commissions” set up after the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) by a fatwa (ruling) issued by Islamic Republic founder Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Many of the victims were supporters of the Mojahedin-e Khalgh (MEK) opposition group, but communists, members of Fadaian-e Khalgh, and other groups were also targeted. The prisoners were secretly killed in prisons throughout the country and dumped into mass graves. Pourmohammadi (and Raisi) were key participants in the commissions.

In the interview, Pourmohammadi also warned that the “war” with the MEK was ongoing: “We still haven’t settled scores. We will respond to all questions after it’s all settled.”

The Iranian authorities have a long history of depicting critics of the state as “enemies of the state,” and prosecuting them harshly under national security crimes. Yet for thirty years, they have denied or ignore the 1988 mass murders. CHRI is deeply concerned that the statements by judicial advisor Pourmohammadi are an attempt to legitimize those extrajudicial killings, and as such pave the way for an intensification of the unlawful punishment of dissidents in Iran.

- CHRI calls on Iranian Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi to disavow statements defending the extrajudicial punishment of prisoners and ensure that extrajudicial punishments will not be used to silence critics and political opponents.

- CHRI also calls on UN human rights bodies, including the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran and the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, as well as governments worldwide, to publicly condemn Pourmohammadi’s remarks and to forcefully note the illegality of the 1988 killings.

“Pourmohammadi’s blatantly false narrative regarding the 1988 mass executions is an attempt to erode any chance for accountability of those who committed these crimes,” noted Ghaemi.

Even during war, governments are obligated to protect the rights of non-combatants and civilians, regardless of their political or religious affiliation. Moreover, the prisoners were killed in extrajudicial proceedings that ignored judicial process.

Pourmohammadi was the Intelligence Ministry’s representative in Tehran’s Evin Prison when he was appointed by then-Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini to one of the “Death Commissions” in charge of the executions. The Commissions were formed following an offensive launched by the MEK from its base in northern Iraq into Iranian territory in July 1988.

Asked about the execution of prisoners who were not on the battlefield but rather serving their sentences, Pourmohammadi said: “What should we have done with [a prisoner] who had been handed operational instructions with escape plans to capture [Khomeini’s residence in] Jamaran and kill the Imam and his companions, and raid the radio and television organization and occupy state offices? Should we have said he’s just an auxiliary, not a frontline combatant? You have to fight everyone who is on the side of the enemy.”

Mosalas, the publication that interviewed Pourmohammadi, is published by Mostafa Ajorlu, a former commander in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

This is not the first time Pourmohammadi has defended the 1988 massacres. Speaking to a group of officials in Lurestan Province in August 2016, he said: “We are proud of carrying out God’s commands against (the MEK) and standing and fighting with the enemies of God and the People.”

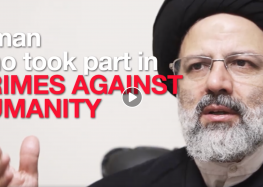

Another “Death Commission” Member Is Now Iran’s Judiciary Chief: Ebrahim Raisi

Another member of the infamous Commissions was Ebrahim Raisi, who is now Iran’s Judiciary Chief.

“Raisi has always been a key player in this regime, as deputy judiciary chief or when he was a member of the Death Commission [in the 1980s] and now as the head of the judiciary,” said prominent human rights lawyer Karim Lahidji in an interview with CHRI in March 2019.

“When he was appointed by [the Islamic Republic’s founder] Khomeini to the Death Commission, he was a young man of 26 or 27 with no theological or legal training. He was appointed because the plan was to kill and purge the prisoners. He has remained a major player during the past four decades.”

The Islamic Republic has never formally acknowledged the mass executions, and no official that participated in them has been prosecuted. Indeed, in a reflection of the culture of impunity that surrounds the perpetrators of those crimes, those who participated, as Raisi and Pourmohammadi demonstrate, have been rewarded with high-level posts in the ensuing 30 years.

1988 Executions Were Indefensible Under Law

Pourmohammadi’s excuse, that the Islamic Republic was at war with the MEK, does not justify stripping its imprisoned supporters of their rights, nor those of the many other prisoners who were executed without any ties to the organization. The executions were carried out swiftly after prisoners refused to sign a letter of repentance, not because they had plans to escape and fight the state (see Justice for Iran’s comprehensive report).

According to Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, “In time of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed, the States Parties to the present Covenant may take measures derogating from their obligations under the present Covenant to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation, provided that such measures are not inconsistent with their other obligations under international law and do not involve discrimination solely on the ground of race, color, sex, language, religion or social origin.”

As such, the argument that the executions were a legitimate response to war-time conditions is not valid because even such conditions would not have allowed the Islamic Republic to carry out the mass extrajudicial killings of prisoners already serving issued prison terms. These murders violated Iran’s commitments under multiple international conventions.

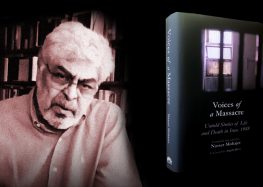

The Iran Tribunal, an international legal tribunal established at The Hague, Netherlands, by the families of victims and comprised of prominent international judges, referred extensively to the mass executions, where “thousands of prisoners were secretly executed in the summer of 1988” in its February 2013 final judgment on its Case Concerning the Gross Violations of Human Rights and Commission of Crimes Against Humanity by the Islamic Republic of Iran.

“People must know what really happened in their country (in 1988),” said Ahmad Montazeri, the son of the once heir apparent to Iran’s first supreme leader, in an interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) in May 2017.

Montazeri continued, “The four members of the (Death Commission) can come forward and tell the truth. Perhaps they could defend themselves by explaining how and why the executions took place and take the opportunity to apologize to the people. Transparency is the best way forward. Coming clean would be a service to themselves and to their country’s history.”

The 1988 Crimes Continue with Harassment of Victims’ Families

In addition, the 1988 executions are not a closed chapter, reflecting events of decades ago. These crimes are in fact ongoing, as detailed in a report by Amnesty International. The thousands of families of those who were killed are still not allowed to conduct mourning rituals or commemorations, and they continue to be harassed, threatened and attacked whenever they have tried to seek justice or even information about their loved ones’ fate, remains or burial sites.