Security Agencies and the Prosecution of Online Activists

In addition to the Iranian state’s efforts to develop the technological infrastructure of Internet control, the Judiciary and security organizations have also pursued the identification and prosecution of online activists. This is done through a variety of organizations, some of them official, some semi-official, and some that are almost completely opaque, facilitating a near complete lack of accountability.

FATA, THE IRANIAN CYBER POLICE

On January 23, 2011, the Iranian national police force established the Cyber Police, also known as FATA, as the cybercrime unit of the national police force.

In addition to fighting cybercrime, the officials justified the formation of the force as necessary to fight terrorism, and to guard against alleged threats to national security. However, FATA’s activities also include monitoring the activities of civil and political activists. During the ceremony establishing FATA, Chief of Police General Esmail Ahmadi Moghaddam said, in an explicit reference to the role of online social networks in the protests following the disputed 2009 presidential election, “Social networks on the Internet brought a lot of harm to our country because of spreading rumors and allowing anti-state groups to help each other.”

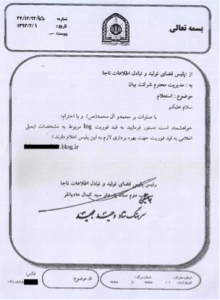

Image of FATA cyber police’s letter to the Bayan company, pressuring them to reveal customer information.

In essence, FATA pursues, through harassment, arrest, and interrogation, any citizen who expresses dissenting views online. Indeed, FATA officials have publicly boasted that they monitor all Internet activity around the clock. FATA’s arrest of Sattar Beheshti, the 35-year-old blogger who died under torture while in FATA’s custody in November 2012, only a few days after his October 31, 2012, arrest, is indicative of their aggressive pursuit of online activists.

The FATA cyber police have also pressured Internet providers to provide them with evidence they can use to pursue online activists. One Tehran-based company, Bayan, publicized FATA’s attempts to illegally obtain personal information about one of its online customers, publishing copies of four letters exchanged with FATA, including one in April 2014 in which FATA demanded that the company immediately hand over the activity records of a user for “necessary action.” Bayan resisted FATA’s demands and wrote to its customers on May 7, 2014: “Carrying out our mission in protecting the privacy of our customers requires technical and legal expertise. Therefore one of the difficult, time-consuming and expensive aspects of our company is the legal department whose activities are largely unknown to our customers. The following is an example of these efforts to protect the rights of our customers.”

CYBER ARMY

As its name signifies, Iran’s Cyber Army is the offensive arm of the state’s cyberspace activities, charged with attacking and bringing down any domestic website that engages in activities the authorities perceive as transgressive—as well as hacking and disrupting the websites of perceived foreign enemies.

Iran’s Cyber Army was created by the Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC) in the wake of the 2009 protests that followed the disputed presidential election in Iran that year. The protestors heavily utilized online platforms to mobilize and organize their protests, and as such the Guards sought to control all online channels of communication, especially social networks, in order to prevent the protestors from utilizing them. They began their activities by posting pictures of the protesters (so that they could be targeted for harassment and turned in to the authorities) and hacking Green Movement (the reformist political movement that arose in the wake of that election) and other opposition websites.

In early March 2010, Gholamreza Jalali, the head of the Ministry of the Interior’s Passive Defense Organization, announced that the “Cyber Warfare Headquarters of the Islamic Republic” would be established soon and invited the cooperation of “good intentioned” hackers. In an interview with the Mehr news agency on March 13, 2010, General Ali Fazli, the Commander of the Revolutionary Guards, formally confirmed the existence of the Cyber Army within the Guards and said it consisted of “experts from among Basiji academics, university students, religious seminary students, and Basiji sisters (female Basiji militia members).” Ebrahim Jabbari, commander of the Ali Ibn-e Abitaleb division of the Guards in Qom told Fars news agency on May 21, 2010, that not only had the Guards formed the Cyber Army but that it was “second in the world.” And in December 2011, Mojtaba Zolnour, the deputy commander of the Guards at the time told the weekly Noh-e-Day that while Iran was new in the field of cyber war, the use of the Cyber Army had resulted in successes in “hacking, disabling, and filtering enemy sites.”

The Iranian Cyber Army has taken specific responsibility for hacking websites such as Radio Zamaneh, the Green Wave of Freedom, Twitter, China’s Baidu search engine, Amir Kabr University newsletter, and Jaras, an opposition news site. In addition to bringing down websites it disapproves of, the Cyber Army also produces malicious botnet programs, which attack a targeted site by marshaling broad attacks involving many (unsuspecting) computers in the attack. According to a report in zdnet.com, one Cyber Army botnet attack infected some 20 million computers through the Windows operating system.

While the Cyber Army is a unit of the Revolutionary Guards, its actual structure and makeup are opaque and its lines of authority blurred. Its shadowy nature facilitates the lack of accountability it enjoys as it carries out its mission, namely the extension of state repression into cyberspace. Indeed, the effective anonymity of the Cyber Army is critical to its central role—to monitor, hack, and bring down websites that are perceived as posing a potential challenge to the authority of the government—and its ability to function extra-judicially, carrying out disabling attacks on websites and removing these voices of dissent, without court order or any responsible official that a citizen or organization can question or hold accountable.

All of the various organizations typically work together. For example, material that is obtained by a hacking operation is then used in the arrest and interrogation (and, frequently, torture) of targeted individuals by police, intelligence, and security officials, and then the illegally obtained online content, as well as the forced confession elicited under torture or threat during interrogation, is then used to convict the individual in court under typically vague national security-related charges.

SECURITY ACTIONS BY OTHER ORGANIZATIONS

Other state organizations, official and semi-official, are active in the persecution of online activists as well. In fact, arrests of such individuals have increased since Rouhani’s August 2013 inauguration, reflecting intensified efforts in this area by hardliners in the security and intelligence services.

For example, on December 3, 2013, the Narenji website posted a note on its site that members from its technical and writing teams had been arrested by units of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards. The arrested included Ali Asghar Honarmand, Abbas Vahedi, Alireza Vaziri, Nasim Nikmehr, Maliheh Nakhaie, Mohammad Hossein Mousazadeh, and Sara Sajadpour. The Narenji website was active in reviewing new information technology tools. In 2010, it received the award for Best Information at the Third Iranian Websites Festival and in 2013 Germany’s Deutsche Welle Persian radio service named Narenji the Best Persian Blog. On June 19, 2014, Yadollah Movahed, the public prosecutor of Kerman, said that eleven cyber activists in the city had been tried and condemned to between one and eleven years in prison (seven of which had been arrested in October 2013). Movahed did not reveal their names but said they were in connection with the Pot Shargh Guashir case, which is Narenji’s parent company.

The effective anonymity of the Cyber Army is critical to its central role—to monitor, hack, and bring down websites that are perceived as posing a potential challenge to the authority of the government—and its ability to function extra-judicially without court order or any responsible official that a citizen or organization can question or hold accountable.

In addition to the arrest of the Narenji members, the public relations office of the Revolutionary Guards in Kerman announced on December 22, 2013, that the Guard’s intelligence unit in Kerman Province had hacked nine “anti-Islamic sites” in an extensive cyber operation, including Neday-e Sabz-e Azadi, Sabznameh, Norooz, Ostanban, 30mail, Nogam, Iran Opinion, and Degarvajeh. “The anti-Islamic sites, which had been set up with millions [of dollars] in financial backing and support from internal seditious elements, were completely blocked from access,” Fars news agency quoted in its report.

Revolutionary Guard agents also arrested the online activist Moslem Boushehrian on January 22, 2014, according to the Jaras website, as he entered Tehran’s international airport. Boushehrian had been studying in China in recent months and was active on social networks. He was reportedly taken to an unknown location and, as of this writing, his family has still not been able to locate him, despite numerous visits to judicial centers seeking his whereabouts, or learn of any charges that have been filed against him. On January 25, 2014, three social network activists, Sasan Jannatian, Siavash Jannatian, and Reza Alenasser were arrested in Mashhad. News reports indicate that as they were leaving Azad University dormitory they were picked up by several armed agents with walkie-talkies and were forced into two cars. Siavash Jannatian was a student at Mashhad’s Azad University and had an active student blog. Sasan Jannatian had previously been detained as a student activist during the 2009 protests. Reza Alenasser had also been previously summoned and warned by security agencies in Khuzestan Province regarding his blog, “Kankash” (Inquiry).

Judicial officials have done their part to ensure hefty sentences to those convicted of transgressions online— at times to an extent greater than that allowed under Iranian law. In July 2014, for example, eight young Iranians were sentenced for their activities on Facebook by Branch 28 of the Tehran Revolutionary Court under Judge Moghisseh to prison sentences that were up to three times longer than permissible under Iran’s own laws.

The official news agency, Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) reported on July 13, 2014, that the individuals were convicted on charges of “assembly and collusion against national security,” “propaganda against the state,” and “blasphemy, insulting Heads of Branches, and insulting individuals.” If the case had been handled according to the law, even at maximum sentence, none of them should have received more than 7.5 years in prison. According to Article 134 of the New Islamic Penal Code, which was implemented in May 2014, if a suspect faces three or more charges, the judge must only rule for the maximum punishment of one of those charges. However, they received, in order of descending severity, 21 years, 20 years, 19 years and 91 days, 18 years and 91 days, 16 years, 14 years, 11 years, and 8 years in prison. All charges that were brought against these individuals were based on content and photographs they had posted on their Facebook pages. The IRNA report indicated that it was units from the Revolutionary Guard’s Sarallah Base that had arrested them.

These few examples are representative, not comprehensive. Yet they demonstrate that multiple official and semi-official organizations, including those whose remit does not specifically pertain to Internet issues, pursue online activists and IT professionals who disseminate technological information online. Indeed, this pursuit has not only has continued, it has intensified.